Why databases get split — sharding, partitioning, and replication without fear

System design fundamentals

Imagine keeping all your clothes in one drawer.

At first, it’s fine - a few shirts, some jeans.

But then seasons change, new clothes arrive, and suddenly the drawer won’t close.

You try to push harder. Nothing helps.That’s what happens when a system grows - and your single database can no longer fit everything inside. It’s time to split the drawer.

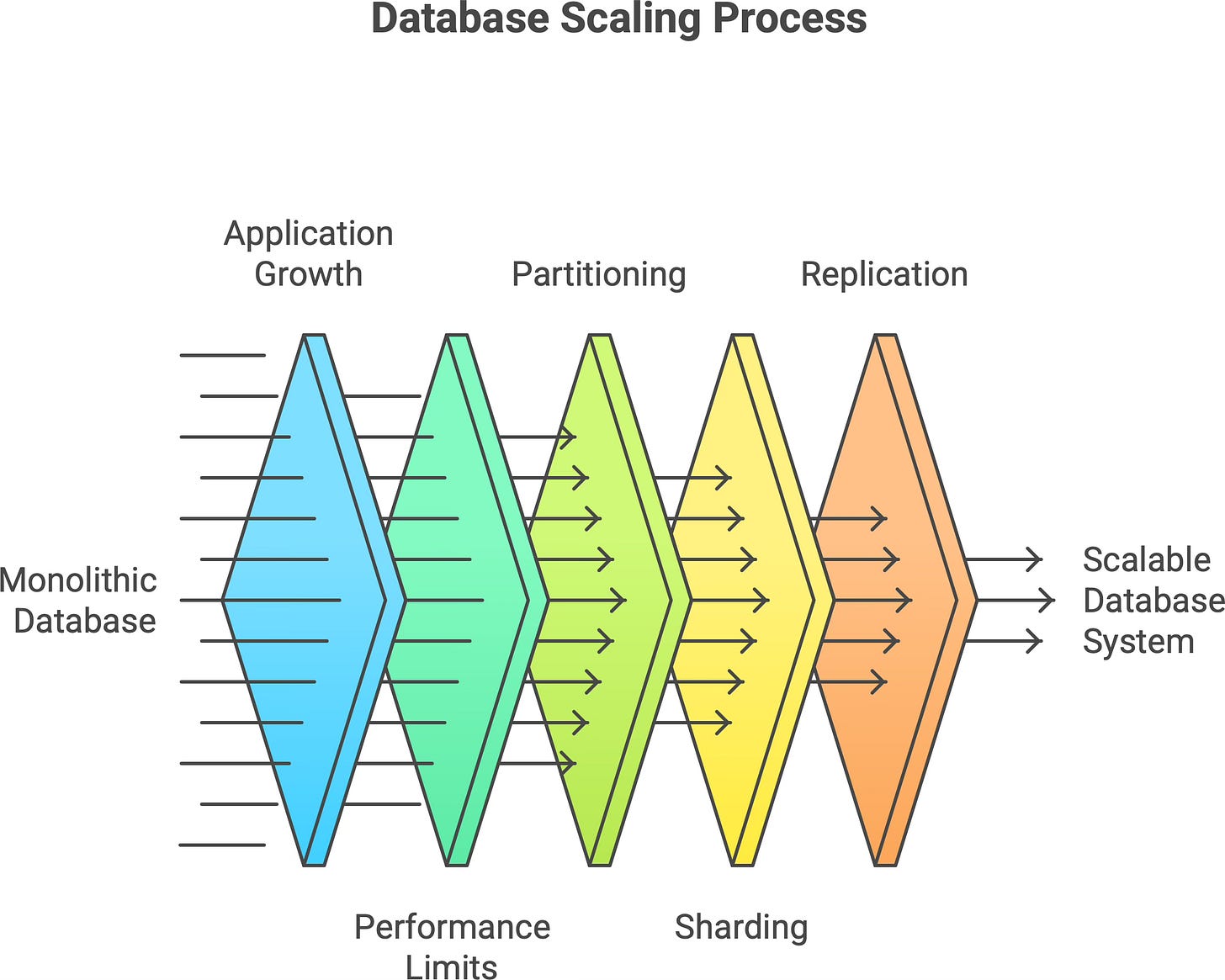

In tech terms, that overstuffed drawer is like a monolithic database. As your application grows, you eventually reach a point where no matter how much you try to squeeze in (or how powerful you make the server), one database just isn’t enough. Splitting a database can sound scary, but it’s a natural evolution when your data outgrows a single container. In this post, we’ll explore why and how databases get “split” through partitioning, sharding, and replication - demystifying these concepts so they’re not so fearsome after all.

🧩 When one database isn’t enough

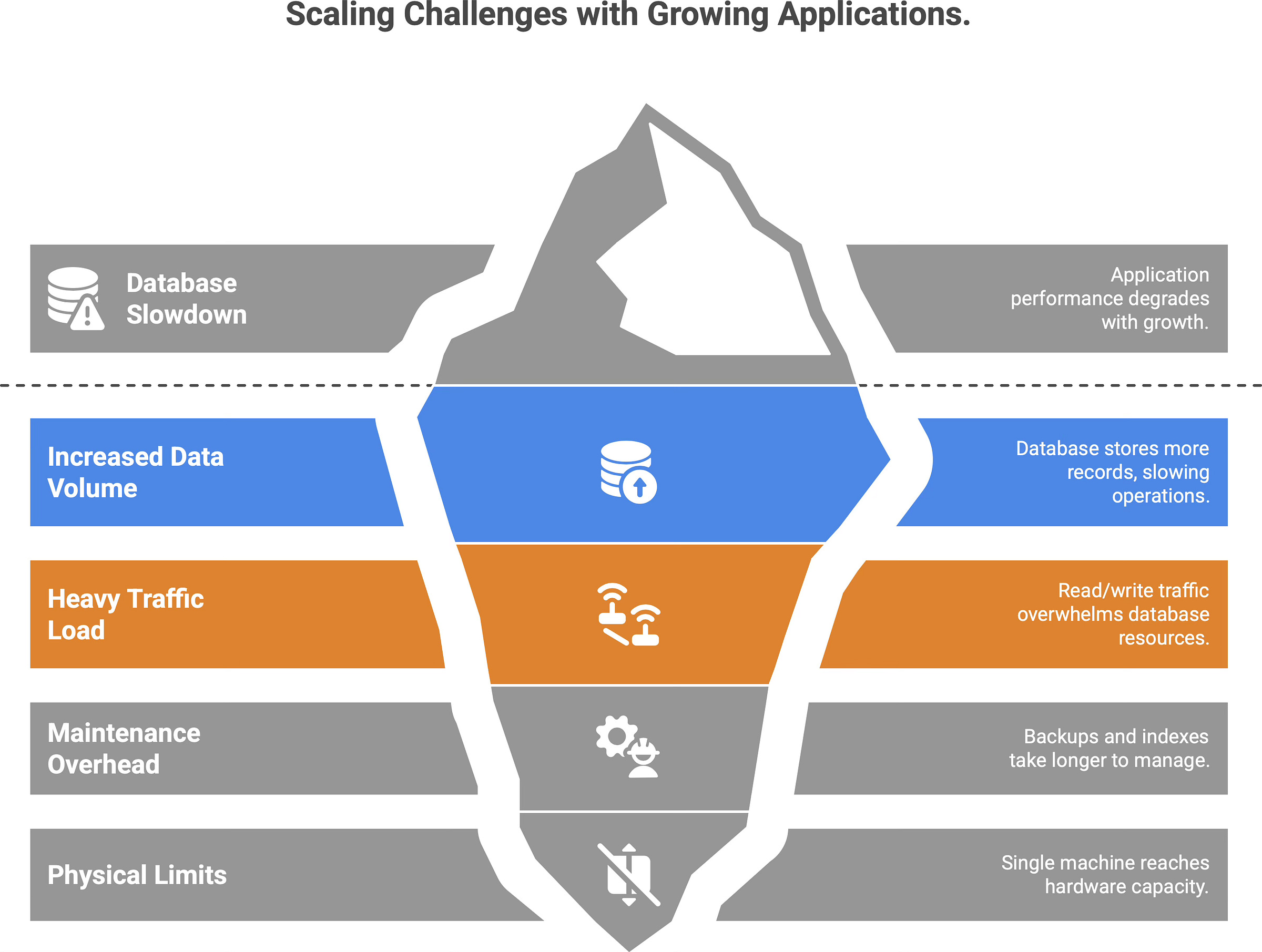

At a small scale, a single database can handle all your application’s data and queries easily. But as the application (and its user base) grows, problems start to appear:

More users → more data: The database has to store more and more records, and operations on a single giant dataset inevitably slow down.

More activity → more load: Heavier read/write traffic can overwhelm the database’s CPU, memory, or disk throughput.

Maintenance overhead: Backups take longer, indexes grow larger, and routine queries or reports start dragging due to the sheer volume of data.

You can try to scale vertically (add more CPU, RAM, or a faster disk to the database server) to get relief. This helps for a while, but only up to a point. Every system reaches a stage where adding hardware is like pouring water into a full glass - it just spills over. In other words, a single machine will eventually hit a physical limit, no matter how beefy it is.1 Beyond that, continuing to push growth on one database is impractical (or outright impossible) - it’s time to scale out by splitting.

⚙️ Three survival strategies — partitioning, sharding, and replication

So, how do we “split the drawer” in practice? There are three fundamental strategies (often used together) to divide and conquer a growing data set. The table below gives a quick overview:

Partitioning organizes. Sharding scales. Replication protects. Each addresses a different problem of scale. Let’s dive into each one and see how they work.

🔁 This is usually where things start to click.

If this made databases feel less scary, it might help someone else too.

Share this article with someone who’s afraid of scaling.

🧮 Partitioning — organizing data so it makes sense

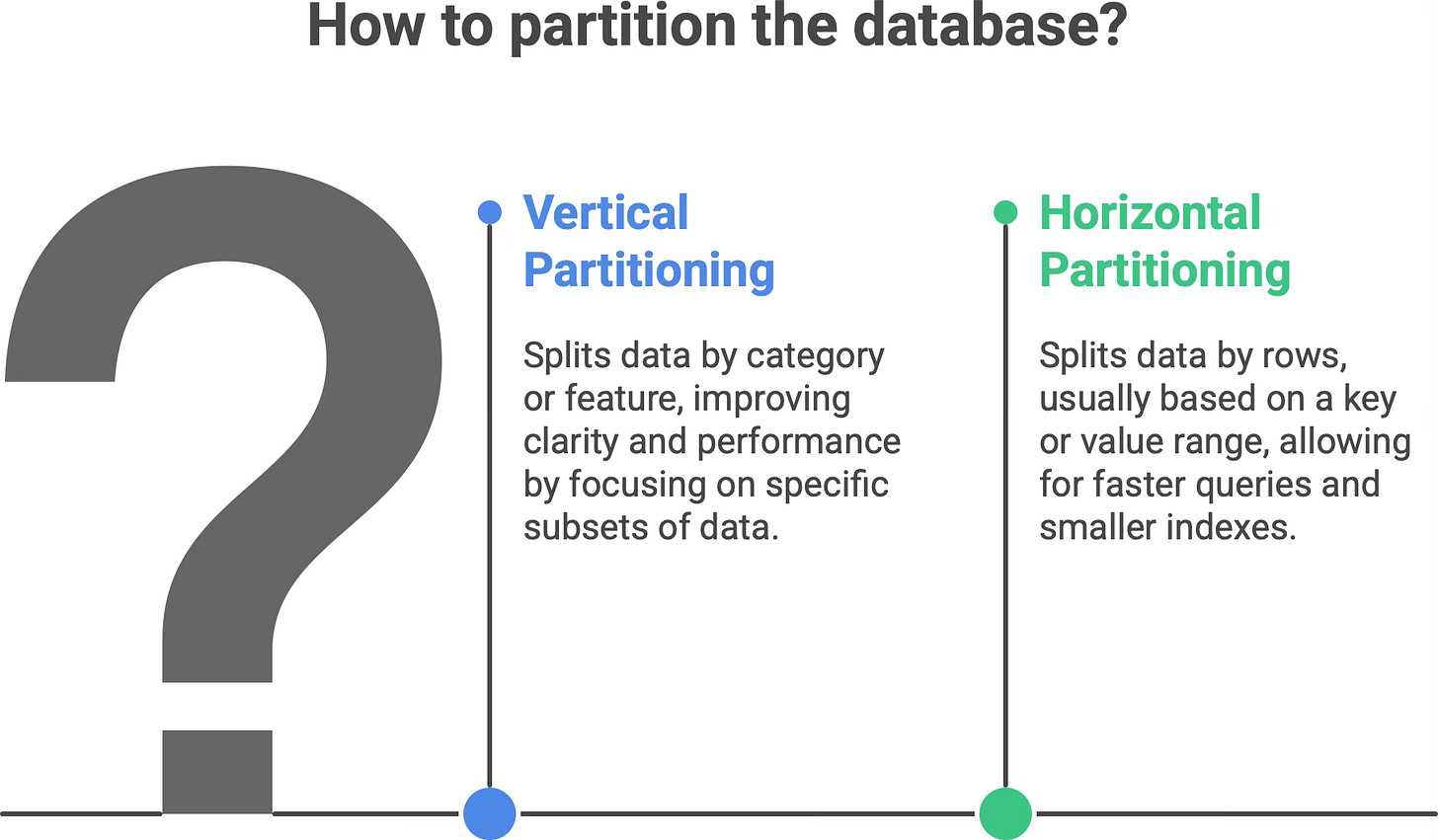

Partitioning means dividing one big dataset into smaller, more manageable chunks. Instead of one monolithic table or collection containing everything, you break it into pieces that are easier to work with. The goal is to group related data together and separate unrelated data, which improves clarity and performance.

There are two common forms of partitioning.

Vertical partitioning. Splitting data by category or feature. For example, an e-commerce application might keep user profiles in one set of tables and order history in another. In relational terms, this could mean putting different functional domains in different tables or databases (or breaking a very wide table into multiple tables by columns). Each vertical partition holds a subset of the columns/fields. Frequently accessed fields might live in one partition, while rarely used or very sensitive fields live in another. This way, each partition is focused on a specific subset of the data (often reflecting a particular feature or usage pattern).

Horizontal partitioning. Splitting data by rows, usually based on some key or value range. For example, you could partition a customer table so that customers with last names A–M are in one partition and N–Z in another, or split a huge log table by month. Each horizontal partition contains a subset of the rows but has the same schema (columns) as the others. Often, horizontal partitioning is implemented as “ranges” (e.g. IDs 1-1,000,000 in one partition, 1,000,001-2,000,000 in the next) or lists (explicit groups, like region codes or alphabetical ranges).

Why partition at all? Because each partition is smaller than the whole dataset, queries and index lookups can be faster - they only scan a relevant subset of data rather than everything. For example, if you partition a log table by date, a query for “last month’s logs” only needs to read the partition for that month, not the entire year’s data.2 Smaller chunks of data also mean smaller indexes and working sets, which can fit into memory more easily and speed up performance. Partitioning can even help with caching: if one subset of data is “hot” (frequently accessed) and others are “cold”, you could keep the hot partition in memory or on a fast disk, and the cold partitions on cheaper storage. For instance, stable, rarely-changing data (say, product descriptions) might be stored in one partition that you cache aggressively, while dynamic data (stock levels) is in another partition that gets updated regularly.

Another benefit is manageability: it’s easier to maintain and back up a 100 GB partition than a single 1 TB monolith. You can backup or restore one segment at a time, or even take one partition offline without affecting others, etc. Partitioning can also improve availability by isolating faults - if one partition (on one server) crashes, the others can still function, so it’s not a total outage.

In short, partitioning is like organizing your wardrobe. Instead of one chaotic closet where everything’s piled up, you have separate sections: shirts here, jackets there, pants in another. Each section is easier to search through on its own. Likewise, a partitioned database is neater and more efficient: related data stays together, and queries can target just the right “section” instead of rifling through everything.

🌍 Sharding — when you need more than one database

While partitioning often refers to splitting data within a single database system, sharding takes it one step further: it spreads the data across multiple database servers. In fact, sharding is basically horizontal partitioning, but done across servers or instances, not just within one. Each shard is an independent database holding a slice of the overall data, and all shards share the same schema structure (they have the same tables/collections, just different rows).

Sharding is a classic approach to horizontal scaling. Instead of pushing the limits of one big machine, you use several machines in parallel - each handling only a portion of the workload. For example, imagine a service with millions of users. Rather than keeping all user records in one database server, you could split users between two shards: say, User IDs 1 - 1,000,000 on Shard A (Server A) and User IDs 1,000,001 - 2,000,000 on Shard B (Server B). If a user with ID 500,000 logs in, the application knows to check Shard A; if ID 1,500,000, it goes to Shard B. The key that determines which shard to go to (here, the user ID) is called the shard key. The application (or a routing service) uses the shard key to direct each query to the right shard.

Sharding can also be based on other schemes. For instance, a social media platform might shard by geography: users from North America on one database instance, Europe on another, Asia on a third, etc. This way each shard handles a region’s users, potentially reducing latency by keeping data geographically close to its users. The important point is that each shard contains a distinct subset of the data and collectively the shards make up the entire dataset.

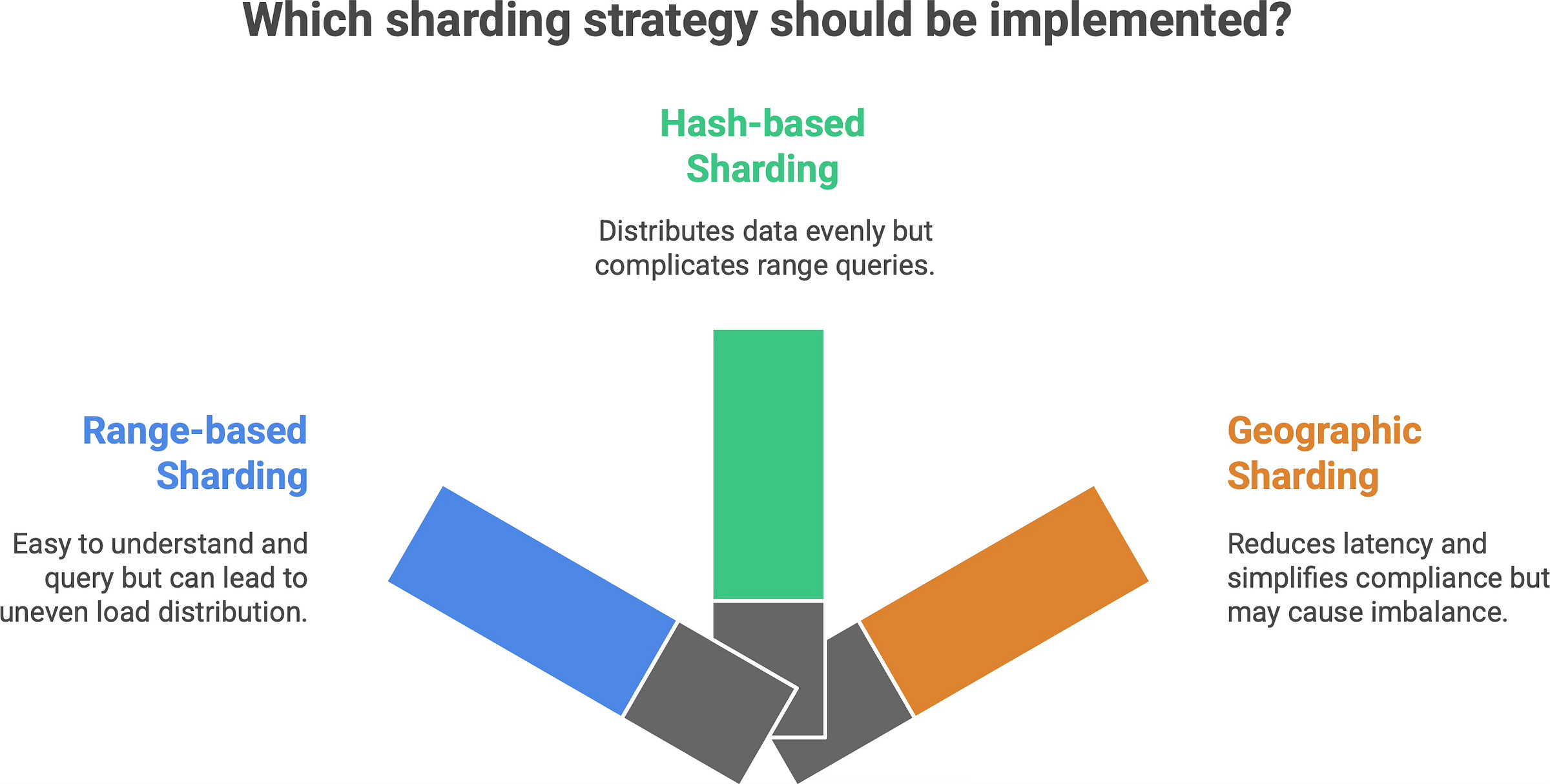

How do we decide who gets what in a sharded setup? There are a few common sharding strategies.

Range-based sharding. Each shard owns a continuous range of data values. For example, shard 1 has IDs from 1-1M, shard 2 has 1M-2M, etc., or one shard has “A-G” customers, the next has “H-N,” and so on. This approach is easy to understand and to query when you know a specific value’s range (e.g. to find all “A-G” customers, you only hit that one shard). However, range sharding can lead to uneven load if the data isn’t uniform. In the alphabet example, one shard might end up with a ton of data (if many last names start with S, for instance) and become a hot spot. Using the first letter of a name would cause an unbalanced distribution because some letters are far more common than others. In such cases, the shard holding “S” or “M” might struggle while others sit mostly idle.

Hash-based sharding. To avoid the imbalance of simple ranges, many systems use a hash function on the key. The hash (perhaps modded into a number of buckets) determines which shard the data goes to. This tends to distribute data evenly in a pseudo-random way (so “Alice” might go to Shard 1 and “Zelda” to Shard 3, regardless of alphabetical order, if their hashed IDs differ). The big advantage is avoiding any one very heavy shard - no obvious pattern means load is spread out. The trade-off is that related items might not live together, and queries that need a range of data (say, all users in California, or IDs between 1000 and 2000) won’t be neatly contained in one shard. Cross-shard queries become more complex, since you might have to ask every shard and then combine results. In other words, hash-based sharding sacrifices some query flexibility for balance.

Geographic or domain-based sharding. This strategy uses a natural segmentation of your user base or data domain. For example, you shard by region (as mentioned) or by customer type (free vs. premium customers on different shards), etc. The benefit is often lower latency and localized failures - each shard can be placed physically closer to its users and handle their specific load. It can also simplify compliance (e.g., European user data stays on an EU server). However, if one category has a lot more users or activity than another, you can still end up with an imbalanced situation. You also have to deal with global queries (aggregating data from all shards) in application logic, since the database no longer has everything in one place.

Sharding is like opening new branches of a library. Imagine a single central library that’s become too crowded - people wait in long lines, it’s slow to find books, and it’s running out of space. The solution: open one branch on the north side of town and another on the south side. Now each branch (shard) serves its local neighborhood, storing copies of books relevant to that area or portion of the catalog, but no one branch has to hold all the books. If you know which branch has the book you need, you go straight there. Similarly, with database sharding, the application routes each query to the correct shard that holds that piece of data, instead of every query hitting one monolithic database.

Insight: By scaling horizontally with shards, we trade simplicity for capacity and resilience. A sharded system is more complex to manage than a single database (you have multiple moving parts and distributed logic), but it can handle vastly more data and traffic. There’s no single monster server carrying the entire load, and if one shard server goes down, it only affects a subset of users/data rather than bringing everything down. In short, sharding sacrifices the convenience of one-stop querying in order to gain virtually unlimited scalability.

🔁 Replication — when safety matters more than speed

Partitioning and sharding split different data across spaces - but replication is about duplicating the same data across multiple places. When you replicate a database, you make one or more copies of it on separate nodes. These copies stay synchronized (often with a small delay) by copying over every write/update. Why do this? Redundancy. If one database instance crashes, or if you simply need extra read capacity, having replicas of the data keeps the system running without interruption.

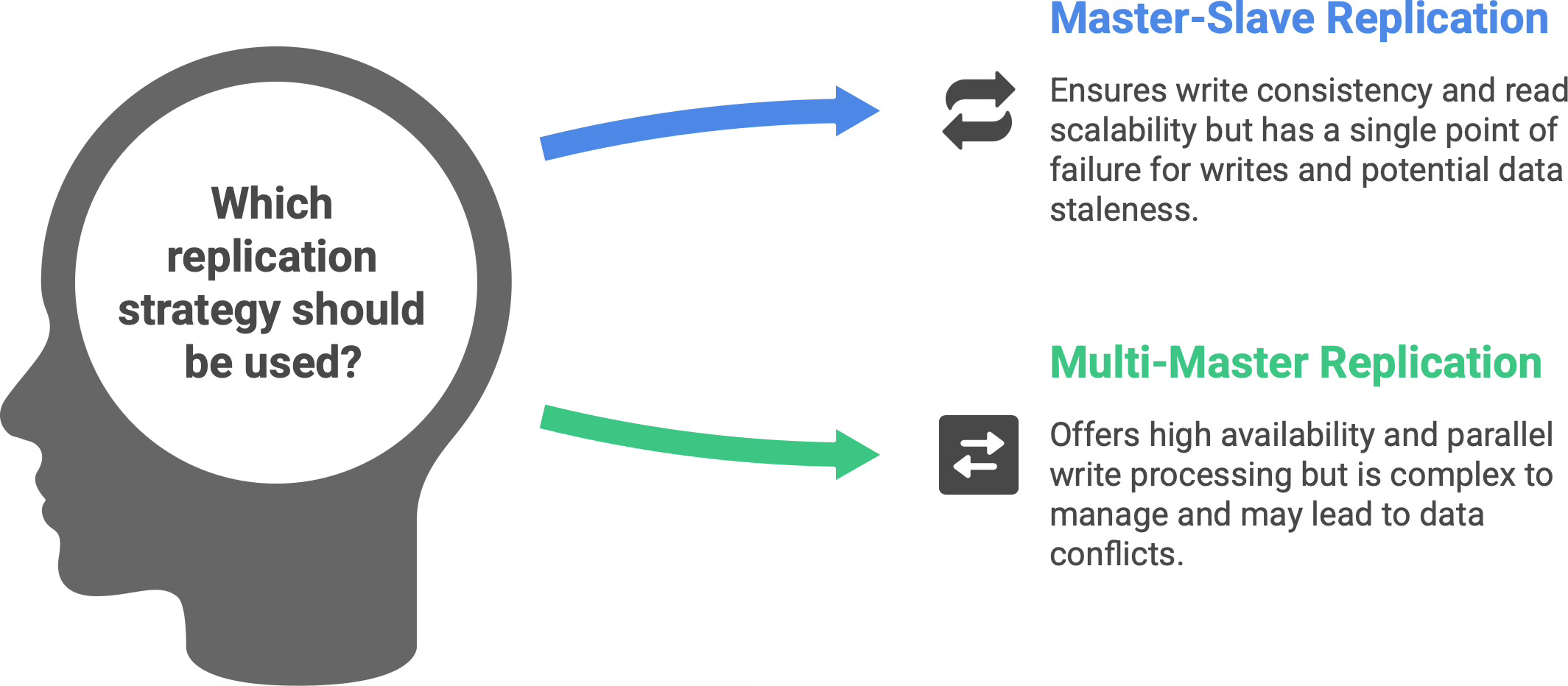

In formal terms, database replication is the process of copying and maintaining database objects (like tables, records, whole states) across multiple nodes to ensure data redundancy, durability, availability, and often better performance.3 Instead of a single point of failure, you have backups that can step in, and instead of one server handling all reads, you can spread reads across replicas. There are a couple of common replication setups.

Master–slave (primary–replica) replication. In this classic model, one node is designated the primary (master) server, which handles all the writes. One or more other nodes act as read replicas (slaves) that continuously copy the primary’s data changes. All writes go to the master, which ensures there’s a single source of truth for updates (no update conflicts). The replicas subscribe to the master’s change log and apply those changes to stay up-to-date. Reads, however, can be distributed: your application can query the replicas for read-only operations, thereby offloading work from the primary.4 For example, a popular website might use one primary database for handling user transactions, and 5 replica databases to serve various read-heavy features (like search or analytics queries) in parallel. This improves read scalability without compromising write consistency (since writes all still funnel through the single master). If the master server fails, one of the replicas can be promoted to master - this is a failover mechanism that provides high availability. The drawback to master-slave replication is that the master can still be a bottleneck for write-heavy workloads (all writes have to go to one place) and a single point of failure for writes (during normal operation). Also, replicas are usually slightly behind the master in time - if replication is asynchronous, a recent write might not yet have reached the replica when a read is done, meaning replicas can serve stale data (more on that trade-off shortly).

Multi-master replication. This is a more decentralized approach where multiple nodes can accept writes and replicate to each other. In a multi-master setup, you could have, say, two or three primary nodes (perhaps in different data centers) all processing user updates, and they exchange their changes with one another to converge on the same data state. The big advantage is there’s no single choke point for writing – you can handle writes in parallel at multiple locations, and if one node fails, the others are still live (improving availability). However, multi-master replication is considerably more complex. If two masters change the same piece of data at the same time (a write conflict), the system needs a conflict resolution strategy (last write wins? merge changes? custom logic?). Ensuring consistency is tricky - you often end up with eventual consistency (updates will reach all nodes, but for a short time different nodes might have different data). Multi-master systems must deal with issues like write conflicts, network partitions, and heavier coordination overhead. This approach is used in certain distributed databases and multi-region deployments (so each region can accept local writes), but it requires careful design.

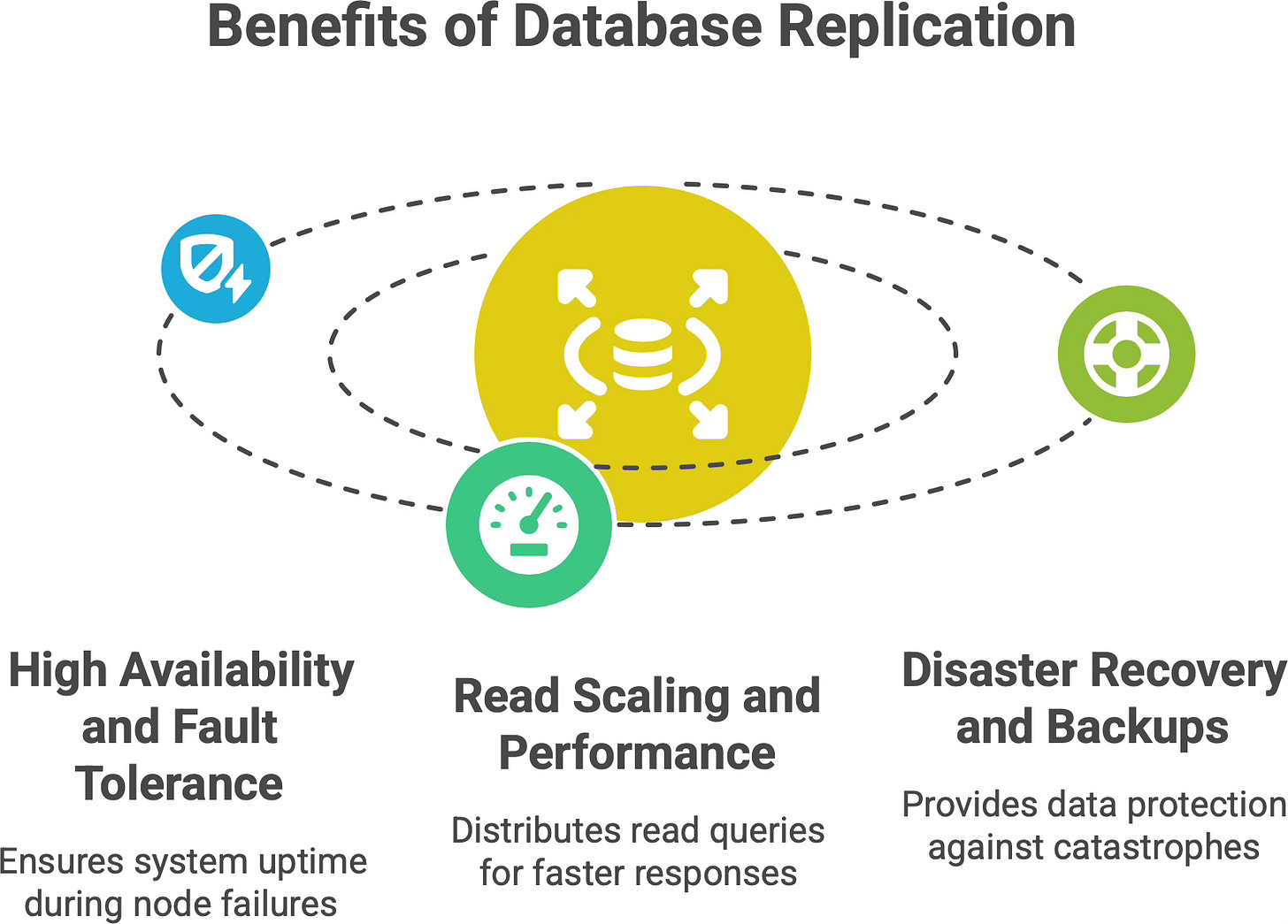

What do we achieve with replication? Primarily:

High availability and fault tolerance: If one database node crashes or becomes unreachable, the system can automatically fail over to a replica which has the same data. The app continues with minimal interruption. By keeping copies in multiple geographic locations, you can survive regional outages as well - one data center’s issue won’t take down the entire service. For example, many cloud databases keep a primary in one zone and a replica in another, so that even a data center outage doesn’t cause data loss or downtime.

Read scaling and performance: By having multiple copies of the data, you can spread read queries among them. As mentioned, a primary-replica setup lets you add read capacity easily - 10 replicas can handle 10× the read traffic of a single server (roughly). Also, if you have users around the world, you might place replicas in different regions. Then a user in Europe can read from a database copy located in Europe, reducing latency, while users in America hit the US replica. Each sees faster response times because the data is geographically closer.

Note: Writes are not scaled in the primary-replica model (all go to the primary), but some distributed databases offer multi-leader or sharded-writes to spread write load too.

Disaster recovery and backups: Replication can be used to maintain a live backup of your database. For instance, you might have your primary in one cloud provider and a replica in another provider or region. If a catastrophe hits one, the other still has your data. Replicas can also be used to run backups or heavy analytical queries without impacting the primary’s performance. Essentially, replication provides peace of mind that one failure won’t destroy your only copy of data.

If partitioning was like organizing your closet, and sharding like opening new library branches, replication is like making photocopies of important documents and storing them in multiple safes. If one safe (or one house) burns down, your documents aren’t lost - a copy exists somewhere else. It’s all about protecting data by redundancy. You pay a cost in complexity (keeping copies in sync) and sometimes in write latency (especially if using synchronous replication), but you gain a lot in terms of safety.

One important aspect to note is consistency: depending on how replication is configured, there may be a lag between a write on the primary and that write appearing on a replica. In asynchronous replication, the primary doesn’t wait for replicas to catch up - it sends the update and moves on - so a replica might be a few seconds (or more) behind. This is known as replication lag, and it means if you read from a replica right after writing to the primary, you might not see the latest data.5 Many systems solve this by directing freshly updated users to the primary (read-your-writes consistency), or by using synchronous replication (the primary waits for replicas to confirm writes, which ensures strong consistency at the cost of higher latency). As an application designer, you get to choose the trade-off: immediate consistency vs. higher performance. In any case, replication gives you the ability to recover or scale reads in ways a single database cannot.

🧠 How these concepts work together

Partitioned tables → Sharded across regions → Replicated for redundancyIn real-world architectures, partitioning, sharding, and replication are not mutually exclusive - they’re often used together in layers to handle different aspects of scale. For example, you might first partition a very large table into subtables by category or date, and then shard those partitions across multiple servers (perhaps by region or hash of a key), and finally replicate each shard to have a standby copy. A concrete scenario could look like this:

You partition your database by function - user data vs. product data vs. logs (organizing by domain).

Within the user data, you shard by region, so EU users are handled by a different server cluster than US users, for performance and regulatory reasons.

Each of those regional shards is replicated to multiple nodes, so it remains available if one node fails.

These strategies can be combined in many ways. In fact, architects recommend considering all three when designing a scalable data infrastructure. It’s common, for instance, to shard data then vertically partition within each shard for manageability. And almost any sharded system will employ replication as well, because more machines mean more points of failure that you have to plan for.

Think of partitioning, sharding, and replication as complementary tools:

Partitioning makes individual databases more efficient by keeping each piece lean and focused.

Sharding allows you to add more machines to handle load by spreading the data horizontally.

Replication makes the system resilient by providing backups and distributed access.

Together, these techniques let modern databases scale without a single node carrying all the burden. A system like Apache Cassandra, for example, automatically partitions data across many nodes and also replicates each piece of data to multiple nodes6 - it’s sharding and replication combined, yielding a distributed store with no single point of failure. Similarly, cloud databases like Google Cloud Spanner or Amazon DynamoDB partition data and keep replicas across availability zones. Even a traditional SQL database like PostgreSQL can be manually sharded and set up with replication.

The key takeaway is that real scalability is achieved by blending these approaches. Each one addresses different challenges of growth (performance, capacity, availability), and together they ensure that as your application scales to millions of users, it remains fast and fault-tolerant. Modern architectures embrace this: your data gets organized, distributed, and duplicated in clever ways so that no one machine is a bottleneck or a single point of failure. It’s truly a dance of speed, scale, and safety working in harmony.

📬 If this helped you see the big picture…

I write about software architecture, systems that scale, and how to reason about complexity without panic.

Subscribe if you want more posts like this - explained calmly and from first principles.

⚖️ The hidden costs — when splitting gets hard

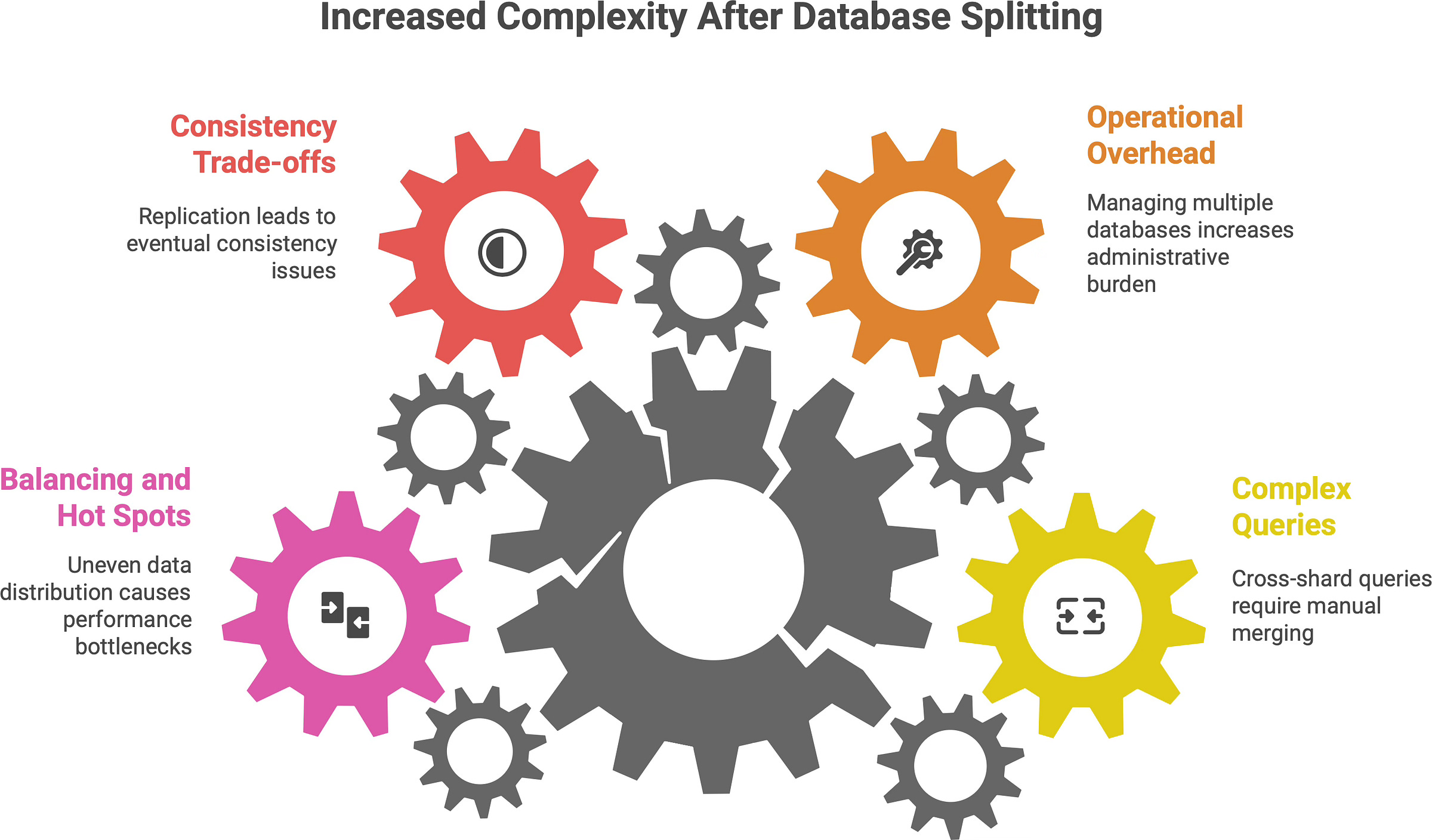

Before you enthusiastically break your database into 100 pieces, it’s important to acknowledge the trade-offs. Splitting a database (through any combination of partitioning, sharding, and replication) introduces complexity. Here are some of the hidden costs and challenges to be aware of:

Complex queries become tricky: When data is all in one place, you can join tables and run analytical queries easily. In a sharded or heavily partitioned system, a query that needs data from multiple shards/partitions is much harder. For example, joining a user profile (in shard A) with that user’s order history (in shard B) might require your application to query both shards and merge the results manually. Cross-shard joins or aggregations are either slow, require additional tooling, or are sometimes impossible. Simply put, distributing data adds complexity to querying - developers need to write more logic, or use middleware, to gather data from multiple sources. This is a big reason why sharding is often delayed until absolutely necessary.

Operational overhead: Running one database is hard enough; running say 10 shards * 3 replicas each = 30 databases can be a headache. More servers mean more things that can go wrong. Routine tasks like backups, restores, schema migrations, or software upgrades have to be performed on each partition/shard, often in a coordinated way. If you change a table schema, you now have to update it across all shards consistently. If you want to back up data, you might have to script backups for dozens of servers. There’s also a maintenance cost in monitoring - keeping an eye on load and health across all the pieces. This increased administrative burden can lead to errors if not managed carefully. In short, a distributed system is harder to manage than a single-node system.

Consistency trade-offs: As discussed, replication (especially asynchronous) can lead to eventual consistency issues - where reads might temporarily see old data until the replicas catch up. Likewise, in multi-master setups, you might get conflicting updates that need resolution. Even in sharded systems, maintaining global constraints or consistency can be challenging. For instance, ensuring a unique username across all shards means each new username might need to be checked against all shards - which is slow - or you accept that duplicates might happen in different shards. Distributed systems often have to choose between strong consistency and high availability (per the CAP theorem). So, splitting data may force you to deal with moments of inconsistency or more complex consistency mechanisms.

Balancing and hot spots: Deciding how to split data is tricky; if you get it wrong, you might end up with an uneven distribution. One shard could become a hot spot - handling a disproportionate amount of traffic or storing much more data than others. For example, if an online game shards players by the first letter of their username, and it turns out most players choose names starting with “S”, then the “S” shard will lag under load. We mentioned range sharding has this risk. Mitigating it might involve re-sharding (splitting a shard into two, or moving some data to another shard) which is a non-trivial operation that can require downtime or careful data migration. Similarly, with partitioning, if one partition grows much faster, you might need to redefine the partition boundaries. Maintaining an even balance as data and access patterns change is an ongoing challenge. It often requires monitoring and possibly auto-scaling or re-partitioning mechanisms to avoid hot spots.

It’s easy to split the wardrobe; it can be harder to find your favorite shirt afterwards. In other words, distributing data solves a lot of scaling issues, but it also means you’ve shifted complexity from hardware to software. You’ll need smart logic to query, integrity checks across shards, robust monitoring, and an ops team ready to handle failures in a distributed environment. These are by no means deal-breakers - every large-scale system deals with them - but they are the “cost of doing business” for scaling out.

💬 The philosophy of scale

Splitting a database isn’t a failure - it’s evolution.

Growth always brings complexity, and architecture is about choosing where to place it.

The best systems don’t avoid scale - they embrace it by dividing their load wisely, ensuring no single node carries the world alone.

In the end, moving to partitioning, sharding, or replication is a sign of success: it means your application grew to the point that a simple approach no longer sufficed. Rather than fearing this complexity, we manage it. Good engineering is not about preventing complexity (which is impossible at large scale), but about organizing complexity in a way that is maintainable and robust. By splitting a big problem (one giant overloaded database) into smaller ones (several well-organized, cooperative data stores), we make the system as a whole more scalable and reliable. No single database carries the entire burden, and that’s a very good thing for longevity.

💬 Every system reaches this point eventually.

Where have you seen things break first - data size, traffic, or reliability?

Share your experience in the comments.

✍️ Recap

One database can’t scale forever - at a certain point, splitting your data becomes inevitable for growth.

Partitioning = organizing a single dataset into smaller segments (by table, column, or row subsets) for clarity and performance benefits (faster queries on smaller chunks, easier maintenance).

Sharding = distributing data across multiple servers/databases for horizontal scalability. Each shard holds a portion of the data, allowing the overall system to handle more load by adding machines.

Replication = duplicating data onto multiple nodes for safety and high availability. If one node fails, a replica can serve the data; plus, read traffic can be spread out to improve throughput.

Real-world systems often combine all three - partitioning for manageability, sharding for scale, and replication for resilience – achieving a balance of performance and redundancy. Embracing these patterns is how we evolve a simple system into one that can handle internet-scale demands without fear.

🤝 Architecture gets easier when we learn it together.

Refer this article to a teammate, or friend who’s learning backend or system design fundamentals.

Appreciate the clarity on consistency trade-offs here. The CAP theorem callout is crucial because so many teams hit this wall once they start sharding and dont realize they've just opted into choosing between availability and strong consistency. I remember one project where we sharded user data by region thinking it would solve everything, but then global analytics queries became a nightmare - had to merge results from 8 shards client-side. The performance win on writes was real tho, just came with that hidden cost of cross-shard complexity you mentioned.