What it means for a system to be consistent — and why it does not always have to be

System design fundamentals

Have you ever sent a bank transfer and noticed it didn’t appear right away?

Or added something to your online cart, only to see it disappear after refreshing the page?Nothing’s broken.

That’s just how distributed systems work - in a world where truth travels in pieces.

In moments like these, it may feel like the digital world is out of sync. But in reality, nothing is malfunctioning at all – it’s simply the nature of distributed systems. Data and truth don’t arrive everywhere instantly; they travel in pieces, catching up from one server to another. This means different parts of a system might briefly disagree on what “truth” is.

Instead of being a binary attribute (consistent vs. inconsistent), consistency in distributed computing is more of a sliding scale – a balance between accuracy, speed, and the realities of networked life. Understanding this balance is key to designing systems that are both reliable and responsive.

💡 Like this kind of thinking?

I write weekly about distributed systems, architecture, and developer-friendly design - all in plain English.

📬 Subscribe here to get the next one straight to your inbox.

🧩 What “consistency” really means

When engineers talk about a system being “consistent”, they mean that everyone (or every part of the system) sees the same data at the same time. In an ideal world, the moment something changes – like you adding an item to your cart or transferring money – all parts of the system would immediately reflect that change. Your friends in a group chat would all see the latest message simultaneously, no matter where they are.

In practice, especially in distributed systems spread across multiple servers or regions, this ideal is hard to achieve. Data often needs time to “catch up” between nodes. One server might record an update a few seconds (or milliseconds) before another. Imagine a group of friends trying to plan dinner over text messages. Some reply instantly, others take an hour. Only after some time does everyone finally agree on the same plan. That’s a pretty good metaphor for eventual consistency – the idea that a system’s parts will eventually agree on the truth, even if they’re temporarily out of sync.

Crucially, consistency isn’t all-or-nothing. It’s tempting to think a system is either perfectly consistent or completely broken, but there’s a lot of gray area in between. We often trade off a bit of immediate consistency to gain other benefits (like performance or uptime). The next sections will explore why those trade-offs exist and how modern systems manage them.

⚙️ The CAP theorem — three letters that changed everything

In the early 2000s, computer scientist Eric Brewer proposed something known as the CAP theorem1. This theorem frames a fundamental tension in distributed systems using three properties:

C - Consistency: All nodes see the same data at the same time. After you write data, any read from any node returns that new data.

A – Availability: The system always responds to requests. Every request gets a response (even if some nodes are down), although the response might not always contain the very latest data.

P – Partition Tolerance: The system keeps working despite network failures or “partitions” that temporarily break the network into isolated pieces.

Brewer’s insight (later formalized by Gilbert and Lynch) was that in a distributed system you cannot have all three of these at once. The CAP theorem famously says: pick two, and sacrifice the third. If you want consistency and availability at all times, your system cannot tolerate certain network failures. If you need to survive network partitions (and most distributed systems do), you face a choice: favor consistency or favor availability. In theory, we’d love systems that are fast, always up, and perfectly accurate; in reality, we’re forced to compromise.

This doesn’t mean a system can never be consistent, available, and partition-tolerant in different moments. Rather, CAP highlights a design priority: when a network partition happens, would you rather your system go offline (to remain consistent) or stay online but potentially show slightly inconsistent data? Different systems answer this question differently, which leads us to CP vs. AP systems.

🧠 How systems choose between consistency and availability

Real-world systems have to make a conscious choice when designing for the CAP trade-off: consistency or availability (since we assume partitions will happen eventually). Depending on the domain, one is often valued over the other.

CP systems (Consistency + Partition tolerance): These systems choose to remain consistent even if it means not always being fully available during a network problem. A classic example is a banking system. If there’s any uncertainty or network hiccup, a bank’s software would rather refuse your transaction or make you wait than show the wrong balance. Accuracy is paramount - no one wants to see money “appear” or “disappear” incorrectly. In fact, when designing a financial system, consistency is considered crucial, even if that means occasionally sacrificing availability. In a CP system, if a few servers can’t talk to each other (a partition), they might halt some operations or switch to a read-only mode until they can synchronize, ensuring no conflicting data gets created. It’s a cautious approach: “Let’s pause until we’re sure everyone’s on the same page”.

AP systems (Availability + Partition tolerance): These systems take the opposite approach: they prioritize uptime and responsiveness, even if it means some parts of the system might be briefly out-of-date. Many social networks and online services fall into this category. You’ve probably noticed that your social media feed will load with older posts rather than showing an error – that’s on purpose. You’d prefer to see something rather than nothing. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram – all these platforms tolerate showing you data that might not be perfectly up-to-the-second, as long as the service stays up and interactive. They embrace eventual consistency under the hood. A new post might appear immediately to the author, while followers see it moments later; such temporary inconsistency is acceptable for the sake of availability and user experience2. In an AP system, even if parts of the network are cut off from each other, each partition can continue accepting requests (reads and writes) and sync up later. It’s a “show something now, fix it later” philosophy.

The choice between CP and AP often boils down to the question: What matters more for this application, absolute accuracy or uptime? In a bank, you’d rather wait a bit longer and see the correct balance (consistency over availability). On Instagram or Twitter, you’d rather see something now – maybe a slightly stale feed – than encounter a “service unavailable” error (availability over immediate consistency). Neither approach is “wrong” - they’re just optimized for different goals.

🧮 Types of consistency (with human analogies)

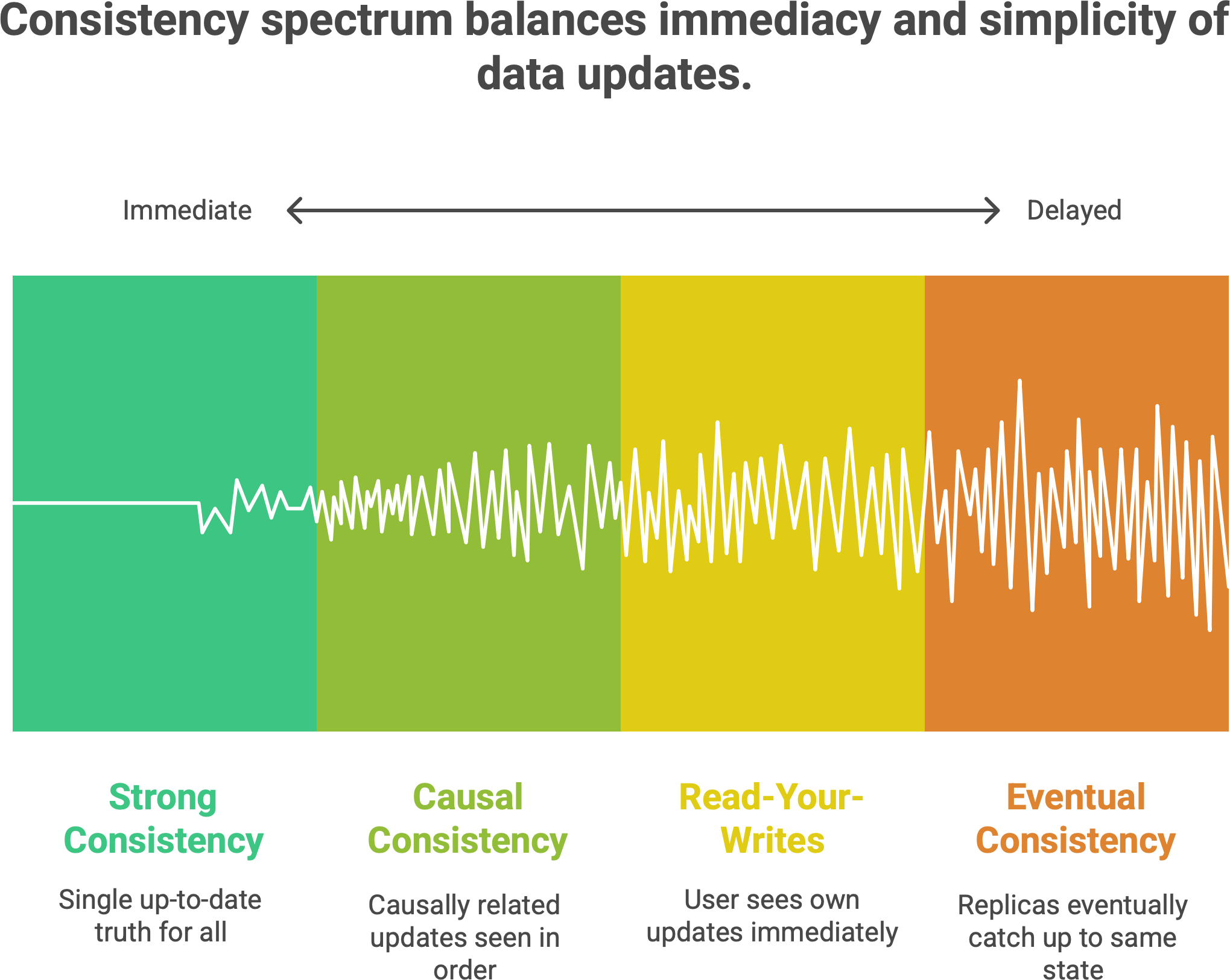

Consistency isn’t a single setting but a spectrum of models, each with its own guarantees about how and when data updates become visible. To demystify some common consistency levels, let’s look at a few in simple terms, along with analogies from everyday life:

Each of these offers a different balance between immediacy and simplicity. Strong consistency is the intuitive ideal – as soon as something changes, every user and every node in the system sees the same latest data. It’s like having a single up-to-date copy of the truth that everyone consults. This is great for correctness, but it can be slow or impractical in a distributed setting (imagine if our group chat required every message to be confirmed by every phone in the chat before anyone sees it – that would be painfully slow!).

At the other end, eventual consistency is very flexible. It doesn’t promise that everyone sees the latest data right now – only that if you stop making updates and wait awhile, all replicas will eventually catch up to the same state. Different users might see slightly different information for a short time, but the differences disappear over time. Many large-scale systems use this model to stay fast and available. It’s like those text messages: you might get replies with delay, but eventually everyone gets all the messages and the conversation makes sense as a whole.

Causal consistency is a bit smarter about ordering – it ensures that causally related updates (like a post and then a comment on that post) are seen in the correct order everywhere3. If event A causes event B, no one will see B without seeing A first. For example, your reply will never appear to have happened before the comment that triggered it. This model relaxes the requirement of strong consistency (which enforces one single timeline for all events) and allows unrelated events to be observed in different orders by different nodes, as long as the cause-and-effect relationships are preserved. It’s a nice middle ground that many systems strive for – improving performance (by not globally ordering everything) without confusing users about what caused what.

Finally, read-your-writes consistency is a guarantee often applied on a per-user basis. It doesn’t concern multiple users agreeing; it just ensures you don’t get confused by your own actions. After you make an update, when you go to read that same data, you’ll at least see your own update reflected4. For instance, if you edit your profile and then refresh the page, the new info should be there for you. Even if some distant server hasn’t gotten the update yet, the system will make sure your reads fetch a copy that includes your changes. This avoids the “Didn’t I just change that?” frustration. It’s a pragmatic way to make an eventually consistent system feel more solid to a user by giving them a consistent view of their own actions.

Insight: Think of these consistency models as different rhythms at which a distributed system reaches the truth. Strong consistency is like a synchronized orchestra – strict but slow. Eventual consistency is more like a jam session where everyone will harmonize, but not instantly. The other models (causal, read-your-writes, etc.) add rules to make the tune sound “right” to the listeners. Modern system design often blends these models, choosing stricter consistency for some operations and looser consistency for others. In fact, many systems treat consistency as a spectrum and mix models as needed – for example, ensuring read-your-writes and causal ordering to keep users happy, while still allowing some eventual behavior for scalability.

🔄 How consistency affects the user

From a user’s perspective, consistency is never about the theory – it’s about how the app feels. Interestingly, users often don’t notice (or care about) whether a system is strongly or eventually consistent, as long as the experience makes sense. The onus is on us as engineers to hide inconsistencies and make things feel natural.

Great systems cleverly mask the quirks of distributed data. A common technique is using optimistic updates on the front-end: when you perform an action (like sending a message or “liking” a post), the app immediately reflects that change in the UI without waiting for the server to confirm. For example, your email application might show a new email in your “Sent” folder instantly, while in reality the server is still in the process of delivering it. This gives you instant feedback. Under the hood, the system will reconcile any discrepancy afterward (if the send fails or the server disagrees, you might see a small “retry” or “syncing…” notice). By showing local results first and syncing in the background, the system feels responsive and “consistent enough” from the user’s point of view.

Another strategy is to mark things as “pending” or “updating”. For instance, a mobile app might display a just-uploaded photo in your gallery right away but with a faint overlay or spinner, indicating it’s being saved to the cloud. You see it immediately, and once the server confirms the upload (or if it fails), the app updates that status (removing the spinner or showing an error). Thus, eventual consistency is happening behind the scenes, but the user experience remains smooth.

💬 Ever noticed this in real life?

Drop a comment below - I’d love to hear your thoughts on systems that felt “off” or surprisingly seamless. What’s one app where you’ve felt the inconsistency (or didn’t, thanks to great UX)?

In other words, the system is eventually consistent, but it feels intuitively consistent to the user. Engineering articles often note that eventual consistency is perfectly acceptable with the right UX design – e.g., showing progress indicators or using short animations to cover up the waiting.

In essence, the goal isn’t perfect data truth at every millisecond – it’s a consistent experience. Gmail, for example, will show your outgoing email as “Sent” immediately, giving you the confidence to move on, even though the message is actually queued and being processed behind the scenes. Social networks show your new status update to you right after you post it (thanks to read-your-writes guarantees), ensuring you’re not confused, while the system takes a bit of time to propagate that update to all your followers. Users are happy because the app behaves in a natural, snappy way – they don’t see the gears turning underneath. A well-designed distributed system often embraces eventual consistency internally but makes it feel almost like strong consistency to the end user.

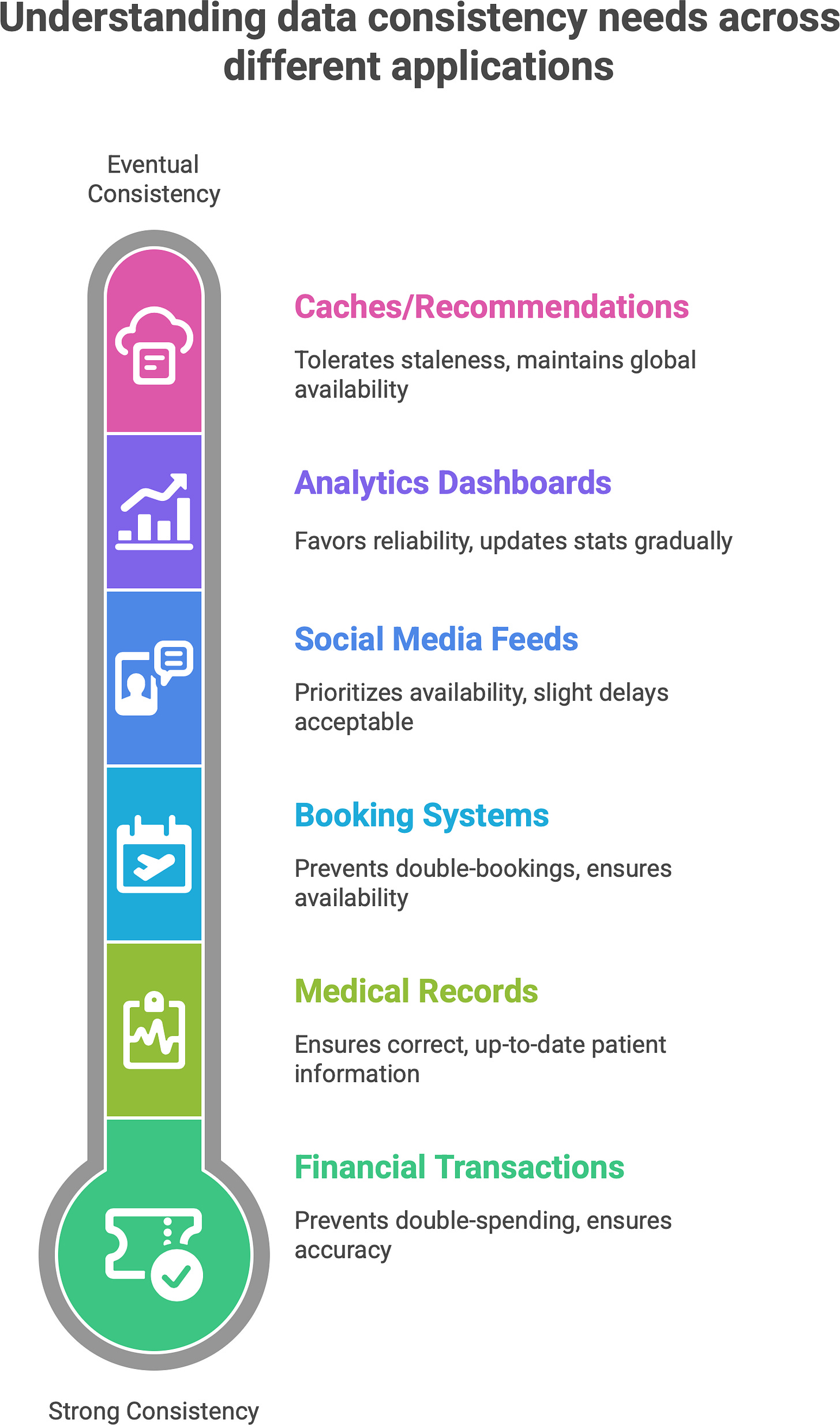

⚖️ When consistency matters most

Not all applications are equal when it comes to consistency needs. Some domains demand that data be absolutely up-to-date and consistent across the board, while others can tolerate a little lag or discrepancy. Knowing which is which helps engineers choose the right approach:

✅ Contexts that demand strong consistency

Financial transactions (banking, payments): Money is serious business. Account balances, transfers, stock trades – these must be correct and consistent globally to prevent errors like double-spending or overdrafts. Banks will often prefer to delay or lock an operation rather than allow an inconsistent view of funds. Similarly, online trading platforms need all traders to see the same prices and account info at the same time.

Medical records: In healthcare systems, showing outdated patient information could be dangerous. If one doctor’s screen shows an old medication list while another’s shows an updated list, the consequences could be life-threatening. For this reason, patient records systems lean toward strong consistency to ensure everyone sees the latest, correct data.

Booking and reservation systems: If two people think they booked the last seat on a flight or the same hotel room because of a momentary inconsistency, you have a big problem. These systems often enforce strong consistency (or use transactions) to prevent double-bookings. It’s better to make one user wait or even receive an error than to allow an overlap that must be fixed later.

✅ Contexts where eventual consistency is fine (even desirable)

Social media feeds: As mentioned earlier, social platforms are a prime example. It’s not critical that every user sees every like or comment the instant it happens – a slight delay is usually unnoticeable, and the system values being always available and fast over being perfectly synchronized.

Analytics dashboards: Dashboards that show website traffic, app usage, or ad metrics typically don’t need up-to-the-second accuracy. If your analytics are a minute behind real time, that’s usually acceptable. What matters is that the system can ingest data reliably and stay up, rather than being perfectly current. These systems often favor availability and partition tolerance, updating stats gradually.

Caches and recommendation systems: Systems that cache data (like content delivery networks, or in-memory caches for database queries) or that serve recommendations (like “people you may know” or product suggestions) can tolerate some staleness. Slight delays in propagation are acceptable and help maintain global availability. For example, an e-commerce site’s “popular products” list might not update instantly with every single purchase; it might recompute every hour. That’s fine – users get quick responses, and the data will refresh eventually without harming the experience.

The guiding insight here is: match the consistency model to the business needs. If a small inconsistency would cause real harm, confusion, or violate trust, that’s when you require strong consistency. If a slight delay or mismatch is essentially invisible or harmless to the user, then “good enough” consistency (and the performance gains that come with it) is usually exactly right. Indeed, strong consistency is crucial for things like banking, booking, and healthcare5, whereas eventual consistency is often a smart choice for high-scale, user-facing systems like social networks, analytics, and caching where speed and availability are a priority.

🧩 Designing with imperfection in mind

Embracing eventual or partial consistency doesn’t mean you give up on correctness – it means you design your system to handle inconsistency gracefully. In fact, building a robust distributed system is as much about planning for things to be temporarily out-of-sync as it is about trying to keep them in sync.

Here are some strategies for designing with these realities in mind:

Define where consistency matters (and where it can relax): Identify which parts of your data must be absolutely consistent and which can be more relaxed. For instance, an e-commerce site might enforce strong consistency for the inventory count of products (so you never sell more than you have in stock), but use eventual consistency for things like the product recommendation list or user reviews. By isolating the truly critical data, you can apply stricter methods there and let other areas enjoy more flexibility.

Use the UI to mask delays: As discussed, a smart UI/UX can hide a lot of inconsistency. Design your user interface such that it doesn’t expose intermediate states awkwardly. If a piece of data might take time to update everywhere, show a loading state, or label it as “syncing…”, or update it in the background. This way, a technical delay becomes a non-issue for the user. A well-timed progress bar or a subtle “refreshing” indicator can turn an otherwise confusing inconsistency into an expected, even reassuring, part of the experience.

Implement repair and reconciliation mechanisms: Since you expect that different parts of the system might diverge temporarily, build in processes that will reconcile data after the fact. This could be a background job that compares and merges divergent copies of data (for example, if two edits occurred separately during a partition, reconcile them once connectivity is restored), or a periodic “anti-entropy” task that ensures all replicas eventually converge. Even simple retry logic can help – if one service fails to get an update due to a network glitch, it can try again later. The system should have a way to heal its inconsistent pieces over time.

Plan for idempotency and conflict resolution: In distributed systems, the same operation might happen twice or out of order due to retries and delays. Design your operations to be idempotent (so that applying the same update more than once has the same effect as doing it once) and define clear conflict resolution rules. For example, if two updates to the same record happen on different partitions, decide which one “wins” or how to merge them (last write wins, merge field-by-field, etc.). Having these rules in place prevents chaos when the system syncs up.

Monitor and adapt: Finally, actively monitor your system’s consistency behavior. Keep an eye on metrics like replication lag (how far apart replicas are), the frequency of stale reads, or how often conflicts occur and get resolved. If you notice issues – e.g., data taking too long to become consistent, or users noticing anomalies – you can adjust your approach (maybe tighten consistency in certain areas, or improve your conflict resolution). Designing for imperfection is an ongoing process of tuning.

A good distributed system isn’t one that never encounters divergent data – that’s nearly impossible at scale. Instead, it’s one that handles divergence intelligently. Think of it like a team that doesn’t panic when members initially disagree; they have processes to discuss and resolve differences and eventually reach consensus. Similarly, your system might have moments where Node A thinks X=5 while Node B thinks X=7. That’s okay if your design ensures they will reconcile (and that users aren’t adversely affected in the meantime). In other words, success is not measured by never having inconsistencies, but by how quickly and safely the system can make peace after a temporary disagreement.

💬 Consistency as a philosophy

Stepping back from the nuts and bolts, there’s a broader way to look at consistency in distributed systems. It’s less about absolute truth at every moment and more about the ability to eventually agree on truth. In life, people don’t always instantly agree or share the exact same knowledge – but with communication and time, they sync up. Distributed systems are similar: they might momentarily hold different views of the data, but as long as they have ways to share updates and resolve conflicts, they will converge on a single reality.

In fact, consistency in distributed systems is as much a philosophy of convergence as it is a technical property. We design protocols (and choose consistency models) to ensure that no matter what happens – even if updates arrive late or out of order – there are rules that will guide every part of the system toward the correct final state. The beauty is that systems, like people, don’t have to agree on everything right away. What’s crucial is that they have a path to eventually reach agreement.

This perspective can be liberating. It means that temporary inconsistency isn’t failure; it’s a normal phase of the system’s operation. By accepting that “truth travels in pieces” and planning accordingly, we make our systems more resilient and often more efficient. We stop chasing perfect consistency at every moment and focus on what really matters: that in the end (often a fraction of a second later, sometimes longer), everyone sees the same result and the world makes sense again.

Consistency, then, isn’t about rigidly enforcing one absolute truth at all times; it’s about ensuring the truth isn’t lost and will be shared. It’s a promise that the system, given enough time and correct mechanisms, can line up all its pieces of truth into a coherent whole. And it’s a reminder that sometimes patience (waiting for things to sync up) and clever design (hiding the waiting, ordering updates) can achieve the best of both worlds – a system that feels fast and fluid for users, yet still converges on correctness behind the scenes.

✍️ Recap

Consistency = agreement between nodes. All users or components see the same data, yielding a uniform view of the system. In distributed systems, achieving this often comes at the cost of speed or uptime.

CAP theorem: In any distributed system, you can’t have all three of Consistency, Availability, and Partition tolerance at once. Because network partitions will happen, every design must choose which to prioritize (consistency vs. availability) when partitions occur.

Many flavors of consistency: It’s not just “consistent or not”. There are multiple levels (strong, eventual, causal, read-your-writes, etc.), each defining how and when a system reaches agreement on updates. These models let us fine-tune the balance between immediacy and performance.

Consistency vs. user experience: Great systems don’t necessarily enforce strict consistency everywhere – they just make the system feel consistent for users. Techniques like optimistic UI updates and careful UI cues (e.g. “syncing” indicators) hide the delays inherent in eventual consistency, so the user trusts what they see.

Right tool for the job: Know when you truly need strong consistency (e.g. finance, medical, critical data) and when “good enough” will do. Often, relaxing consistency in non-critical areas yields huge gains in scalability and fault tolerance.

Design for eventual consistency: Accept that temporary mismatches will occur and build your system to resolve them. Use reconciliation processes, conflict resolution strategies, and clear client guarantees (like read-your-writes) to manage inconsistencies. This isn’t a weakness – it’s a wise design strategy that acknowledges reality.

In summary, consistency isn’t a black-or-white property but a nuanced aspect of system design. The goal is to ensure the system can eventually align on a single source of truth and, in the meantime, keep things running smoothly. By understanding the shades of consistency and learning how to mask or manage inconsistency, we can build distributed systems that are both reliable and user-friendly – systems that don’t always have to be perfectly consistent every split-second, as long as they get there when it counts.

Consistency isn’t a binary “on/off” state in distributed systems. Systems often trade the ideal of instant consistency for better availability, speed, or resilience. What matters is choosing the right consistency model for the job: strong consistency for things like banking or bookings, and eventual consistency for social feeds or caches. Well designed systems mask temporary inconsistency from users, ensuring a smooth experience despite the underlying trade-off.

Super insightful. The CAP method is gold!