No official API⁉️ No problem‼️ How I reverse-engineered Substack API (and so can you)

You don’t need official docs to create real tools - just curiosity and patience

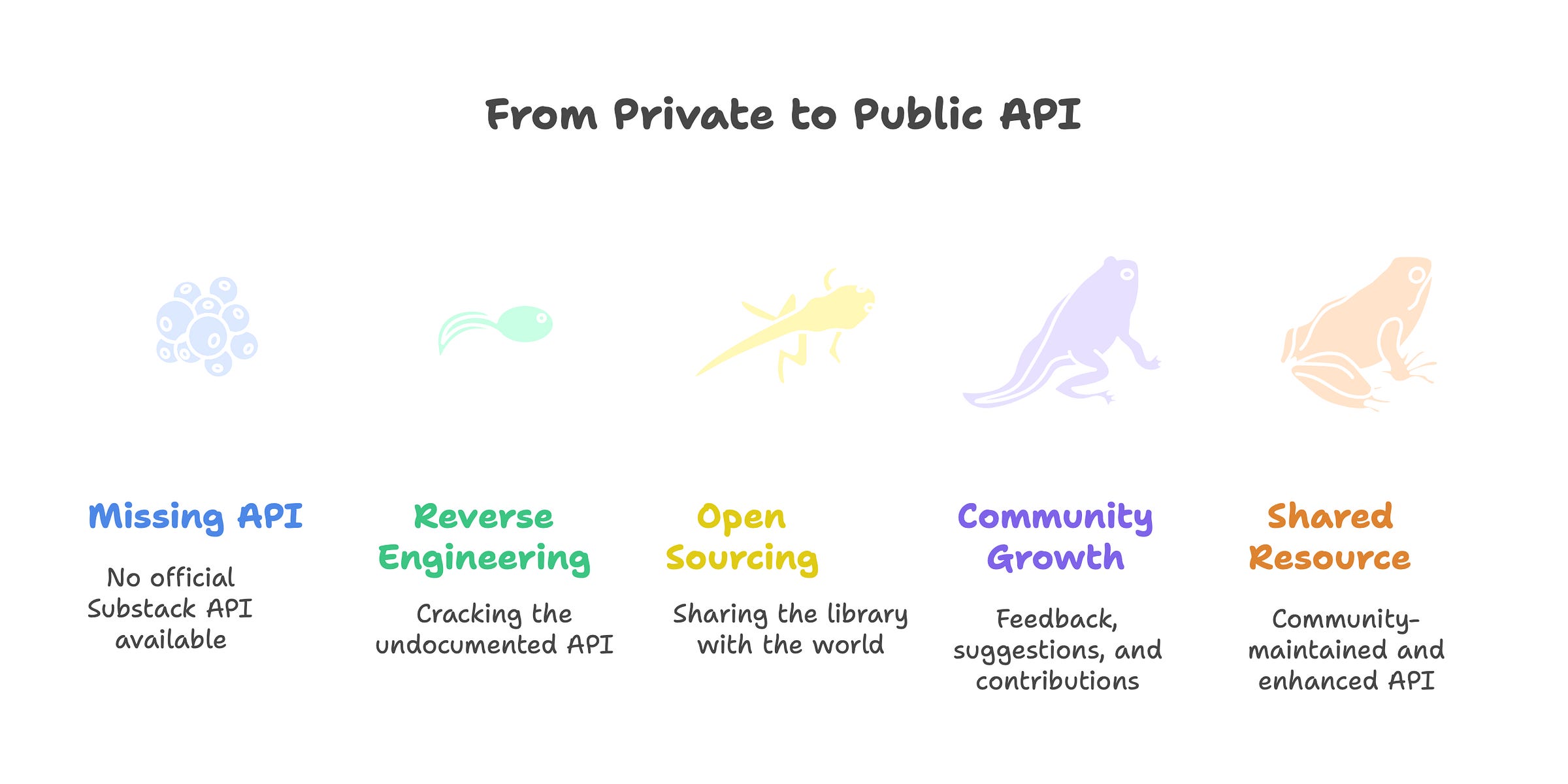

If you’ve ever tried to automate or analyze data on Substack, you’ve probably hit a wall. There is no official Substack API or documentation for developers – a fact that has frustrated many of us. I ran into this roadblock when I wanted to fetch and analyze Substack Notes data (Substack’s Twitter-like feature) as part of an automation workflow. My goal was to use the automation tool n8n1 to gather insights from Notes. But without an API, it felt impossible. As one user plainly put it, “Substack currently doesn’t provide an API for automated posting” – and by extension, no easy way to fetch data like Notes. This was the spark: a mix of personal need and irritation with the lack of a solution.

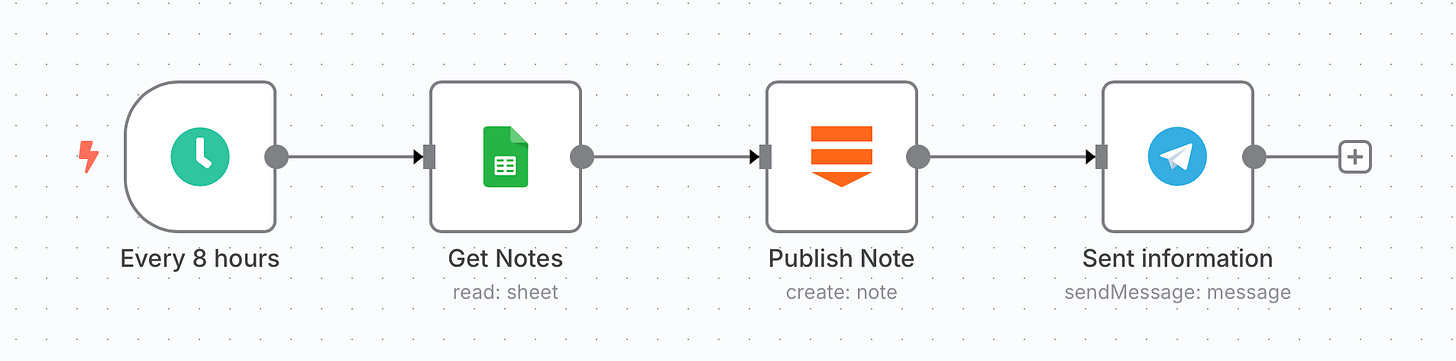

n8n is like LEGO for automation - a visual way to connect tools, APIs, and data without writing full-blown apps. I’ve used it to auto-like Substack Notes, sync posts to Notion, and even monitor trends in comments. Want a deep dive on how n8n works and how it streamlines API-based workflows?

👉 Leave a comment and let me know.

I initially felt stuck. Scraping the Substack website’s HTML was an option, but a messy and brittle one. Substack’s interface is dynamic and interactive, which makes pure HTML scraping unreliable for complex data (like paginated lists of notes or comments). I didn’t want a half-baked workaround; I wanted a real, robust solution. Instead of giving up, this frustration lit a fire in me: what if I could find a hidden Substack API by reverse-engineering how the web app works? 🚀

The missing tool

The absence of an official API wasn’t just a minor inconvenience – it was a glaring gap. I realized I wasn’t alone in this; many Substack writers and developers wished for a way to programmatically interact with Substack, whether for analytics, content management, or custom integrations. Some had resorted to hacks: copy-pasting subscriber info, manually adding emails from external forms, or building custom scrapers. These approaches were tedious and error-prone. It felt like having a powerful sports car (Substack’s platform) but no steering wheel to control it programmatically.

Rather than accept defeat or continue with brittle scrapers, I decided to build the missing tool myself. The idea was to create an unofficial Substack API client – something that could fetch data and perform actions just like an official API would, but without Substack’s direct support. This wasn’t about “hacking” or breaking rules; it was about using publicly available web traffic to create a tool that should exist. I wanted to bridge the gap between Substack’s rich functionality and the developer community that craved to use it. In short, if Substack wasn’t going to give us an API, I’d figure out how to make one.

Why I built it

So why take on this challenge? First, I had a personal need: I wanted to automate my Substack workflows (like analyzing Notes engagement, consolidating data, and maybe even posting or scheduling content) via n8n. Doing this manually or with unreliable scrapers was not sustainable. Second, curiosity – I’ve always enjoyed peeking under the hood of web apps to see how they work. Reverse-engineering can be a fun puzzle, and I had a hunch that Substack’s frontend had some secrets to reveal.

Lastly, I’m a TypeScript enthusiast, and I saw an opportunity to create typed domain models for Substack’s world (think classes like Profile, Post, Comment, Note, etc.). In other words, I wanted a clean, type-safe interface I could use in my Node.js projects. This would make it easier to work with Substack data in a structured way, with the safety of TypeScript’s compile-time checks. The end goal was a library that feels nice to use – something modern and developer-friendly. (In fact, the library I ended up building is exactly that: “a modern, type-safe TypeScript client for the Substack API” with classes representing Substack entities).

How it began

To reverse-engineer Substack’s private API, I had to change how I looked at the website. I asked myself: how does Substack’s web app actually fetch content?

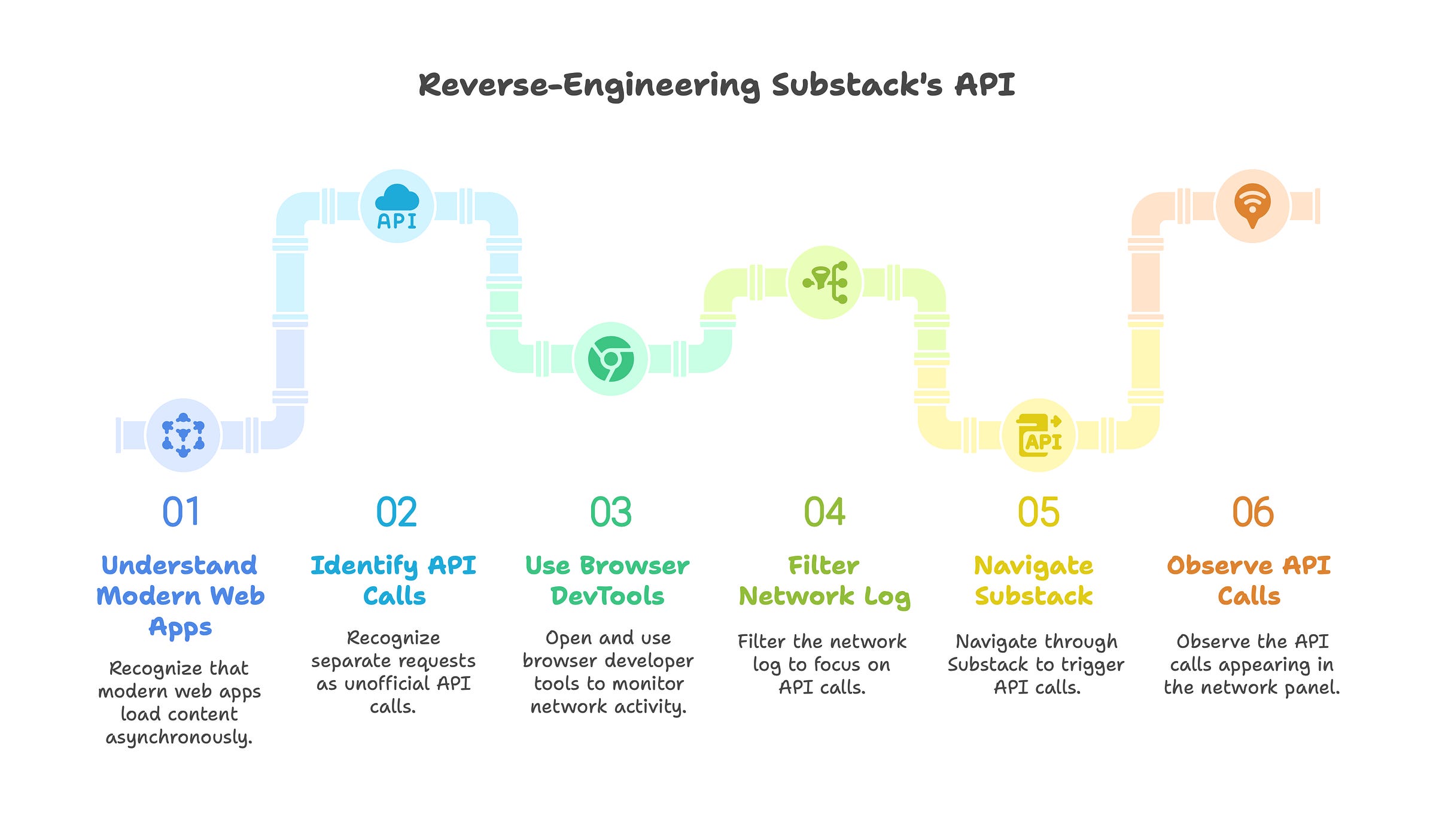

Before modern web apps, websites were simple: when you visited a page, your browser sent a request to the server, which grabbed the data from a database, rendered a complete HTML document, and sent it back - all in one go. Everything you needed was already embedded in the response. No background API calls, no separate fetches. This “server-rendered” model left no APIs for us to explore or reverse-engineer. But today’s apps - like Substack - load data dynamically using JavaScript, making separate requests in the background.

When you load the site, the browser gets a minimal HTML shell, and then fetches real content - posts, profiles, comments - asynchronously through background API calls. The diagram above shows exactly how that works: your browser loads the page, then sends separate requests like GET /api/v1/profile or GET /api/v1/posts to the backend server, which pulls data from the database and returns it as JSON. That shift is exactly what made it possible for me to discover and document Substack’s hidden API. My job was to eavesdrop on that conversation between the browser and the server.

How do you eavesdrop on your browser’s conversations? With the browser’s developer tools! Every modern browser has developer tools (usually opened by right-clicking and choosing “Inspect Element”).

I opened Safari DevTools and clicked on the Network tab. This magical panel shows every request the browser makes – images, scripts, and importantly, API calls. To focus on the API calls, I filtered the network log (e.g., looking for URLs containing /api/ or watching for requests labeled XHR/fetch). Then I started using Substack normally: I navigated through my Substack dashboard, opened the Notes feed, clicked around on my profile. Sure enough, calls began appearing in the Network panel. It was like discovering footprints of a hidden creature – each API call URL was a clue to how Substack’s private endpoints worked.

Cracking the undocumented API

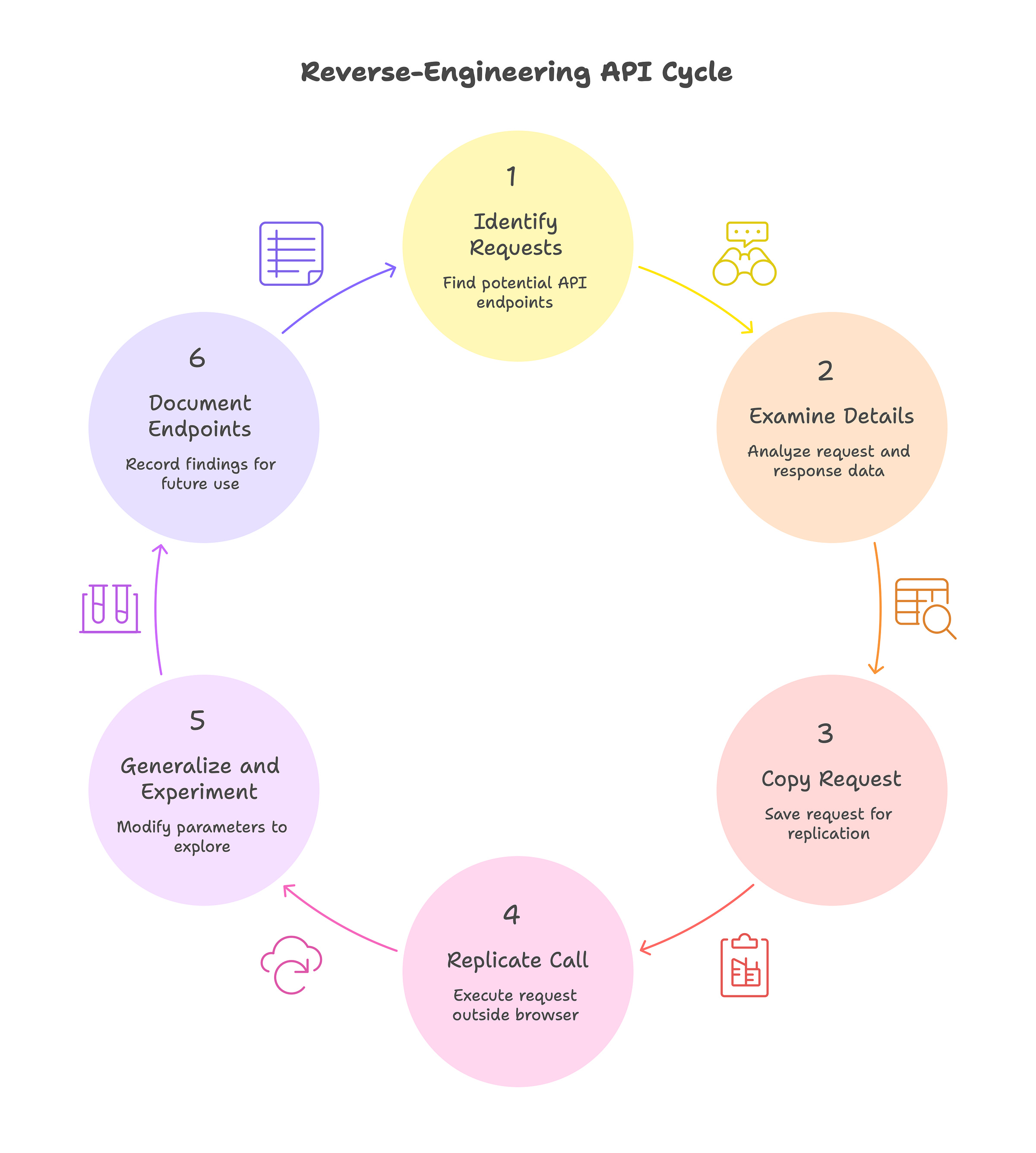

Once I could see the network calls, the real fun began: figuring out what each call did and how to use it myself. I approached this systematically, almost like a detective gathering evidence. Here’s the process I followed.

Identify interesting requests. In the DevTools Network tab, I looked for requests that likely contained the data I wanted. For example, when I loaded the Substack Notes page, I saw a request URL that had notes in it (bingo!). There were others for things like posts, comments, etc. The presence of familiar keywords made it clear these were Substack’s internal API endpoints.

Examine the details. I clicked on each interesting request to inspect its details. DevTools lets you see the URL, the method (GET, POST, etc.), query parameters, and even the response data. The responses were in JSON – human-readable data structures. For instance, one endpoint returned a list of notes with fields like id, content, publish_date, etc. I was basically looking at the data Substack’s own web interface uses.

Copy the request (for replaying). Unlike Chrome, Safari doesn’t let you “Copy as cURL”, so I had to reconstruct the request myself. I copied the full request URL, noted the necessary headers (including auth cookies), and then rewrote it as a curl command line by hand.

Replicate the call with cURL. I opened my terminal and pasted the cURL command. This let me call the same endpoint outside of the browser. Initially, I got a bunch of data back – success! I was careful to include my authentication cookies (Substack uses a cookie called connect.sid for logged-in sessions) in the cURL request. Without authentication, some endpoints would return an error or empty data. With my session cookie, however, I could pull my private data (like my own profile info or subscriber-only posts) just like the browser did.

Generalize and experiment. Once I verified a single request worked, I started tweaking it. For example, if I found an endpoint like /api/v1/notes?cursor=<some_position>, I’d try changing parameters like cursor=<some_position> to see if I get more results, or maybe fetch older notes. I also tried endpoints on different publications: e.g., replacing my Substack’s domain with another publication’s domain to see if I could fetch their public data. Little by little, I mapped out what endpoints exist and what they return.

Document the endpoints. I kept notes on each discovered endpoint – the URL pattern, required parameters, and what data it returns. It felt like drawing a treasure map. For instance, I learned there were endpoints for listing posts, getting a single post’s details, listing comments on a post, retrieving my own profile and the profiles I follow, and yes, endpoints to read and write Notes.

At this point, I essentially had the pieces of an unofficial REST API for Substack. It was undocumented, sure, but it was real and working. I could now fetch my Substack data on demand. Just to illustrate, here’s an example of what one of those calls might look like using cURL:

# Example: Fetch the latest notes from your Substack (requires auth cookie)

curl 'https://<your-substack>.substack.com/api/v1/notes' \

-H 'Cookie: connect.sid=<your_session_cookie>' \

-H 'Accept: application/json'

This isn’t an official documented call, but it’s exactly what the Substack web app does internally. The result is a JSON payload containing the most recent Notes, which I could then parse in code. I repeated this kind of exercise for various features – posts, comments, profiles – each time using DevTools to find the call and cURL (or a REST client) to replay it myself.

Throughout this cracking process, two things became clear:

modern web apps like Substack are built on these kinds of JSON APIs (even if they’re private), and

with some patience, anyone can uncover them.

It’s not magic – it’s just observing and reproducing what our browser is already doing. This realization was empowering, especially for an “unofficial” project like mine.

Open sourcing it

Finding those endpoints was just the first step. The end goal was to create a usable tool – a code library – so that I (and others) wouldn’t have to repeat this detective work every time. I rolled up my sleeves and started coding what would become the substack-api package: an unofficial Substack API client built in TypeScript. My approach was to design the library in a domain-driven way, modeling the key concepts of Substack (users, posts, comments, notes, etc.) as classes or functions in a logical structure.

I wanted the library to feel intuitive. For example, if you have a Profile object (representing a user), you might call .posts() on it to get their posts, or .notes() to get their notes. If you have a Post object, you could call .comments() to fetch its comments. This mirrors real-life relationships: profiles have posts; posts have comments. Under the hood, those methods would hit the corresponding endpoints I discovered (e.g., GET /api/v1/posts/... or GET /api/v1/comments/...), but as a user of the library you wouldn’t have to worry about the URL details – it’s all nicely abstracted.

To give you a taste, here’s a short example in TypeScript using the library:

import { SubstackClient } from 'substack-api';

const client = new SubstackClient({

apiKey: '<your connect.sid cookie value>', // authentication

hostname: 'yourpublication.substack.com' // your Substack domain

});

console.log('🚀 Substack API Client Example\n')

// Fetch your own profile

const myProfile = await client.ownProfile();

console.log(`Hello, ${myProfile.name}! Your slug is ${myProfile.slug}.`);

// Iterate over your recent posts

for await (const post of myProfile.posts({ limit: 3 })) {

console.log(`- "${post.title}" (published on ${post.publishedAt?.toLocaleDateString()})`);

}The code above initializes the client with your session cookie (acting as an API key) and your Substack domain. Then it retrieves your profile and prints your slug, and fetches your latest 3 posts with their titles and dates.

🚀 Substack API Client Example

✅ Using API key from environment variables

Hello, Jakub Slys 🎖️! Your slug is jakubslys.

- "Sharding vs partitioning vs replication: Embrace the key differences" (published on 7/25/2025)

- "Get Your Cert" (published on 7/19/2025)

- "Understanding caching: a beginner’s guide" (published on 7/18/2025)The nice thing is that everything is strongly typed – post.title and post.publishedAt are real properties with proper types. No need to dig through JSON manually each time.

I open-sourced this project on GitHub2. I also published it on npm as substack-api so that anyone can npm install it easily. The library ended up with a robust feature set beyond just reading data. For example, it supports content creation (yes, you can publish a new Note through the API client, just like the web interface does). In other words, it’s not just read-only – it lets you interact with Substack in many of the same ways you can via the website.

The response from the community was encouraging. The library is already being used in other projects – for example, an n8n Substack integration node relies on substack-api under the hood for all its operations.

🚀 Curious what happens when this API meets automation? I’ve already hooked it up to n8n - the open-source ✨ visual automation tool.

💡 Imagine:

📝 Auto-saving your Substack Notes to Notion

📬 Getting real-time alerts when your favorite writer posts

📈 Tracking follower growth without ever opening a browser

👇 Want to see how it works? Drop a comment below!👇

Knowing that my work enabled an n8n integration (so people can now plug Substack into their automation workflows) is incredibly satisfying. It feels like we collectively unlocked Substack’s data and made it available for creative use. And because it’s open source, others can audit the code, contribute improvements, or adapt it for their own needs.

What I learned

This journey taught (or reinforced) several lessons, both technical and personal.

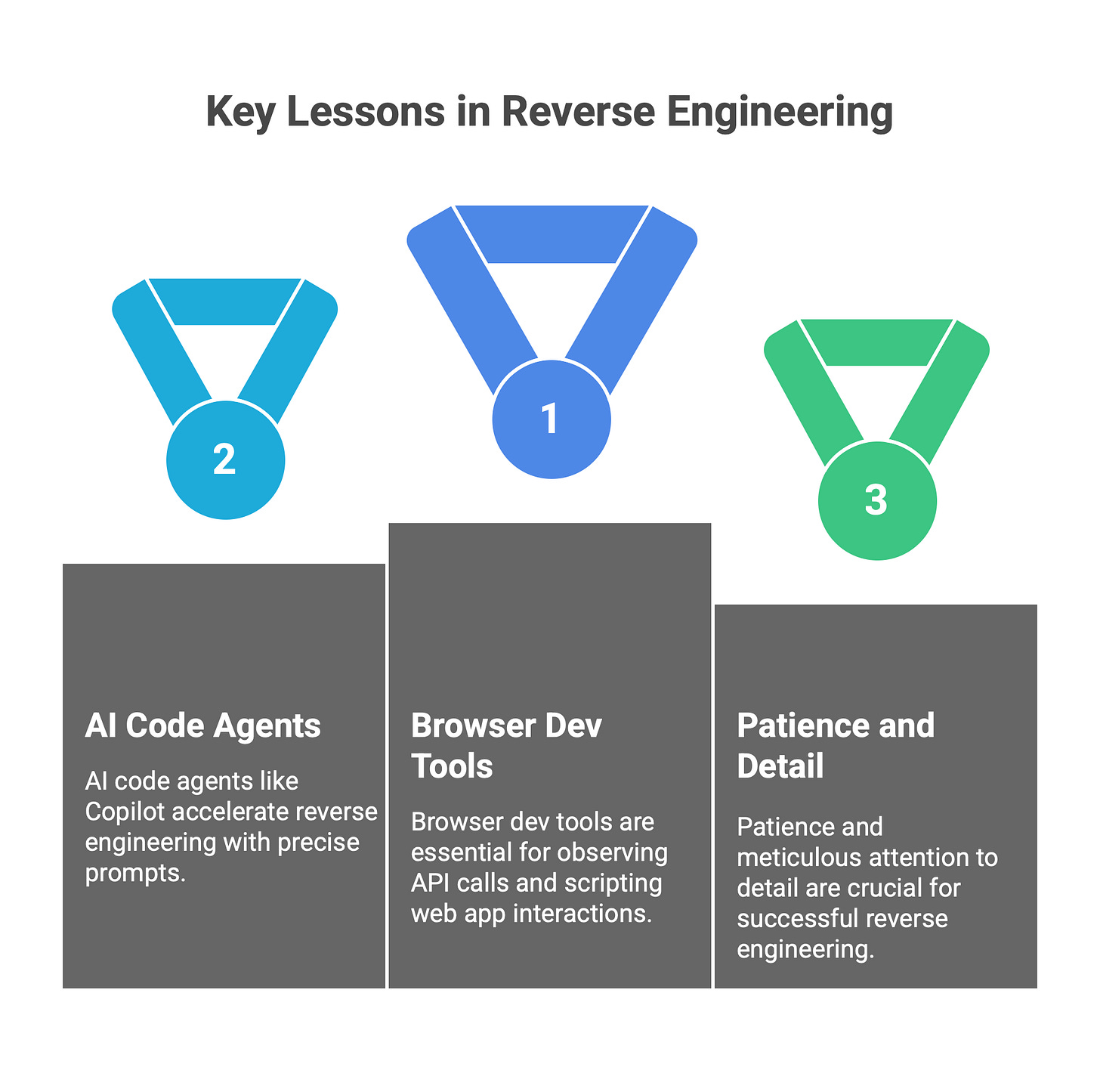

The browser is your friend. I gained a much deeper appreciation for browser dev tools. Learning to use the Network inspector to watch API calls is an incredibly useful skill. It’s like having x-ray vision into any web app. Now, whenever I use a web service that doesn’t have an API, I instinctively pop open DevTools to see what I can find. For anyone new to this, remember: if you can do something in a web app, you can probably script it – you just need to observe how the app talks to the server.

Copilot agents are powerful, but they need precision. One surprising insight was just how useful GitHub Copilot (or other AI code agents) can be when reverse-engineering and writing wrappers around undocumented APIs. From scaffolding API request code to generating type definitions from sample payloads, it accelerated a lot of my work. But I quickly learned that the quality of output depends entirely on the clarity of the prompt. Vague questions led to vague code. On the other hand, if I gave Copilot a clear goal – for example, “convert this JSON into a strongly typed TypeScript interface” or “generate a wrapper for this REST endpoint using fetch” – the results were much better. The tool is powerful, but only when you are precise. It's like working with a junior dev who's lightning-fast but needs clear specs. That mindset made me a better prompt-writer and taught me to think more deliberately about what I was trying to build.

Patience and attention to details. Reverse-engineering isn’t instant. I had to methodically try different interactions in Substack, log lots of requests, and piece together how things work. Missing a header or a small query parameter could mean the difference between an endpoint working or not. I learned to be meticulous – documenting every finding, comparing responses, and double-checking assumptions.

Code design and documentation matter. When building the library, I wanted it to be approachable for others. I invested time in writing clear documentation, with examples and an API reference. This made the project more welcoming and also forced me to understand my own code better. I found that writing docs often highlights edge-cases or API quirks that you might otherwise gloss over. A well-documented project is more likely to attract users and collaborators.

Respect and responsibility. An important takeaway is the ethics of reverse engineering. I was careful that all my work stayed within legal bounds – I used my own credentials, accessed only data I was allowed to (like my own and public data), and did not attempt to break any protections. Reverse engineering web APIs is generally legal when you’re just mimicking normal browser behavior, but it’s important to use such powers responsibly.

In a nutshell, this project was a crash course in web API sleuthing, and it left me with sharper skills and a broader perspective on web development.

What is next

The project doesn’t end here. There are more endpoints and features on my wishlist for the substack-api library. Here are a few things on the horizon.

Integration with N8n. Now that this unofficial API exists, I’m excited to integrate Substack with other parts of my tech stack. One immediate plan is deeper n8n integration – maybe a set of n8n nodes that can, not only read, but also write (e.g. publish a note to Substack as part of a workflow). I also think of things like creating custom analytics dashboards, or even hooking Substack up to an AI (imagine an AI summarizing your Substack stats daily – the sky’s the limit when an API is available).

🤖 Are you into automation? Or curious about it?

🧩 Want to learn how to automate with n8n?

🛠️ Interested in building your own workflows like this 👆 one?

Collaboration and contributions. I’m hoping more developers will join in to contribute code or report issues. Being open source means anyone can suggest improvements. Even simple contributions like improving documentation or writing examples for specific workflows (say, using the API to back up your posts, or to cross-post content) can be super helpful for new users.

Keeping up with Substack. As Substack evolves, the API might change. I plan to keep an eye on it – that means if Substack changes how their web app communicates (say they introduce GraphQL, or change endpoints), I will update the library accordingly so it continues to work. In a sense, maintaining an unofficial API is an ongoing reverse-engineering effort.

In short, I see this project as alive and growing. If you have ideas or needs, you can always open an issue on the GitHub repo. I’m excited to see where it goes next, and I’m open to collaboration.

It is your time now!

By now, I hope you’re feeling inspired to tinker with your own projects. Whether it’s Substack or another platform with an unofficial API, the process is accessible to anyone with curiosity and a bit of patience. Give it a try – you might be surprised at what you can unlock. And if you do, share your story! We learn together as a community when we exchange these experiences.

🔁 Reverse engineering isn't about breaking the rules - it's about understanding the systems we already use every day. I built this tool to automate my work and share the knowledge. You can do the same.

If this post helped or inspired you - drop a star ⭐️ in GitHub , file an issue, or tell me what you’re building. 🚀

Love the fact that you open-sourced it 👍

Enjoyed the walk through even though it’s a lot for my non-technical brain 😁