From TinyURL to Bitly (and beyond): designing a smarter URL shortener

Principles and practice of system design

One rainy afternoon, John, Peter, and Andy huddled around a cluttered desk, frustrated by the clunky URL shortener they were using. They needed to share a long web link for their new project, but the legacy shortener provided only a basic alias and almost no insight into who clicked it. "Why can’t we get more info? It’s 2025, and all we have is a click count!" Peter groaned. John added, "The old tools just shrink links – no smarts, no real analytics". Andy, the visionary of the trio, suddenly lit up with an idea. “Links aren’t just connectors - they’re real-time signals of attention”, he exclaimed, articulating their new vision. In that moment, the three inventors realized they could build something better: a smarter URL shortening system with built-in analytics to understand those “signals of attention” in real time.

They imagined a platform where every short link not only redirects users seamlessly, but also feeds into live metrics – showing which links are getting attention, when, and how. The turning point had arrived. Instead of tolerating limited features, John, Peter, and Andy decided to design their own URL shortener from the ground up. It would be fast, fun, and informative. With excitement brewing, they grabbed a whiteboard to start mapping out their idea. The journey from frustration to inspiration had begun, and next, they would translate their vision into a concrete plan using domain-driven design principles.

John, Peter, and Andy have set the stage: they want a URL shortener that’s more than just a link alias. Now they’ll dive into designing it step by step, starting with understanding the domain of URL shortening and link analytics.

To tackle the design, Andy suggests using an Event Storming workshop – a playful, visual way to map out the domain before writing any code. Armed with sticky notes (both physical and digital), the trio gathers around a whiteboard to brainstorm how their URL shortener should work. Event Storming encourages them to focus on domain events first – significant things that happen in their system – and to derive other elements like commands and actors from those events.1 It’s an approach that feels like storytelling: perfect for our inventors.

The scope 🎯

They start by clearly defining the scope of their domain (🎯). John says, "Let’s keep it focused: we’re building a core URL shortening service with analytics, not an entire social network or ad platform". In other words, their system will handle creating short links, redirecting users, and tracking clicks – nothing more. With the scope nailed down, they move on to identify the key happenings in this domain.

Modelling the domain

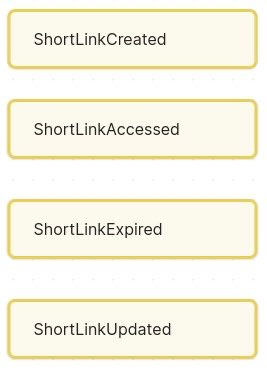

Domain events

🟠 Orange sticky notes

These are the noteworthy things that occur in the life of a link. The team jots down events in past-tense language (a convention in event modeling).

ShortLinkCreated – when a new short URL is generated for a long URL.

ShortLinkAccessed – when a user clicks a short URL (i.e. a redirect happens).

(Optional) ShortLinkExpired – if links can expire, this event would fire when a link passes its expiration date.

(Optional) AnalyticsUpdated – when click data for a link is processed (this might be a result of a batch job or on each click).

Andy explains that these domain events are the heart of their story – each event is a fact that something happened in the system. For example, ShortLinkCreated means “a new short link was generated” – it’s an event the system can record and react to. ShortLinkAccessed means “someone was redirected through the short link”, which is crucial for analytics. By listing events, they’re essentially writing down the story of how their system will be used.

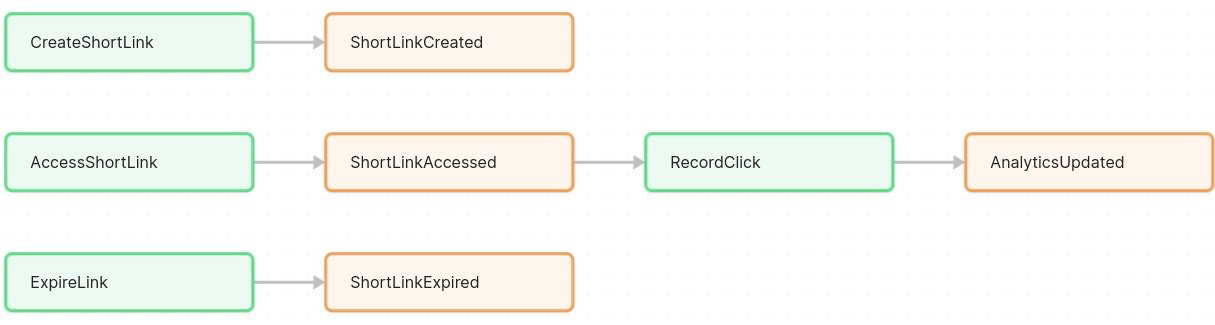

Commands

🟢 Green sticky notes

Next, they consider what initiates those events. Commands are like instructions or actions in the system, often triggered by an actor (user or system).

CreateShortLink – a command when a user requests to shorten a URL. This will result (if successful) in a ShortLinkCreated event.

AccessShortLink – a command when a user (or browser) requests a redirect via a short URL. This would lead to a ShortLinkAccessed event (if the code exists).

RecordClick – a command (possibly internal) to log a click for analytics. This might be triggered automatically when ShortLinkAccessed occurs.

(If expiring links) ExpireLink – a command that marks a link as expired (maybe via a scheduled job or trigger when time is up), resulting in ShortLinkExpired event.

By identifying commands, they clarify what actions the system performs in response to user input or other triggers. For instance, CreateShortLink is invoked by a user inputting a URL to shorten; AccessShortLink is invoked when someone hits the short URL in their browser. Each command leads to one or more events (e.g., AccessShortLink → ShortLinkAccessed, plus maybe an Analytics event).

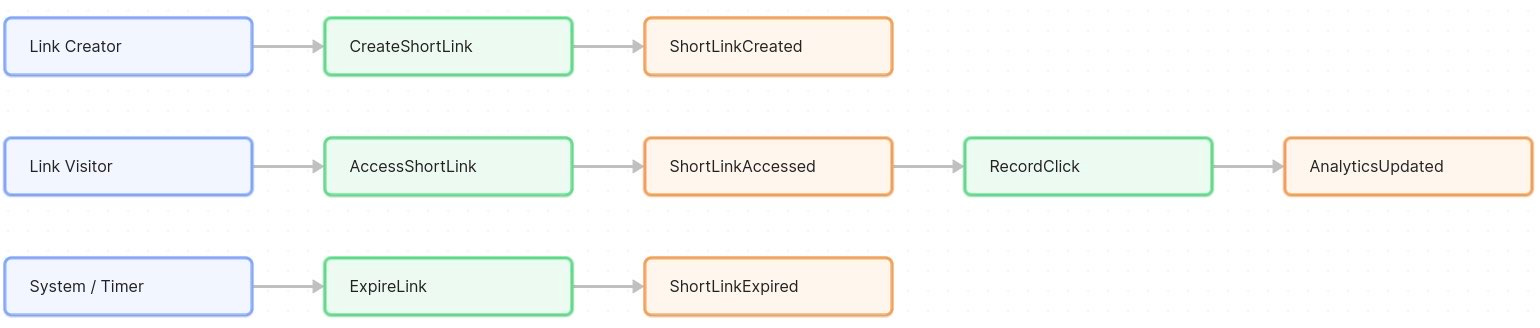

Actors

🔵 Blue sticky notes

Who or what triggers those commands? The team lists the actors – the people or external systems interacting with the shortener.

Link Creator – this is the user who shortens a URL (could be John, Peter, Andy, or any user of the service). They trigger the CreateShortLink command.

Link Visitor – anyone who clicks on a short link. In practice, it’s a web user or their browser triggering the AccessShortLink command by visiting the short URL.

System/Timer – the system itself might act as an actor for scheduled tasks, like expiring links or running analytics jobs (if any automated policy triggers commands).

For simplicity, John notes that the same person might be both creator and visitor at different times, but it’s useful to distinguish their roles. The actors clarify who initiates each part of the process: the creator drives the shortening, the visitor drives the redirect, and occasionally the system’s own background process might drive things like expiration.

Policies

🟡 Yellow sticky notes

Policies represent business rules or decisions that happen in response to events. They are like automatic if-then rules the system should enforce, often leading to new commands. The team discusses a few.

Unique Code Policy: Ensure that each short code is unique. If a generated code collides (unlikely with a good algorithm, but possible), the system should detect the conflict (a kind of hotspot concern) and perhaps generate a new code or fail the operation. This policy might trigger a retry of CreateShortLink with a different code strategy.

Link Expiration Policy: If they allow expiring links, when a ShortLinkExpired event occurs (or when the expiration time is reached), the system should prevent future redirects for that link. This could be implemented by marking the link inactive. A policy might automatically issue an ExpireLink command when the current time passes a link’s expiration timestamp.

Analytics Policy: Every time a ShortLinkAccessed event happens, a policy could dictate: “record this event to analytics”. In practice, this could mean publishing a RecordClick command to the analytics system whenever a redirect occurs. The team decides this will be done asynchronously so as not to slow down the redirect (more on that later).

Policies ensure the system’s business rules are consistently applied. Andy points out that policies often act as glue: an event in one part of the system triggers a command in the same or another part. For example, their analytics policy will listen for the ShortLinkAccessed event and then invoke the RecordClick action in the Analytics component.

Aggregates / Entities

🟣 Purple sticky notes

Aggregates are clusters of related entities that handle commands and produce events. In simpler terms, an aggregate is like a conceptual object in the domain that has an internal state and logic. The team identifies the following.

ShortLink aggregate – representing the short link itself as a business entity. It holds data like the short code, original URL, creation date, expiration date, and perhaps a count of clicks. The ShortLink aggregate’s behavior: it can handle commands like CreateShortLink (assigning a code, saving the mapping) and maybe ExpireLink (mark itself expired). It produces events like ShortLinkCreated and ShortLinkExpired.

LinkAnalytics aggregate – representing the analytical info for a short link. This might be in a separate bounded context (see below). It could handle the RecordClick command and update click counts or other metrics, producing perhaps an AnalyticsUpdated event or updating a read model. In practice, LinkAnalytics might not be a single object but a process that tallies events for each link. For modeling, they treat it as an aggregate responsible for reacting to each ShortLinkAccessed event for a given link (e.g., incrementing a counter for that link).

They note that the ShortLink entity belongs to the core shortening domain, while LinkAnalytics belongs to the analytics domain. Each aggregate will ensure business rules within its boundary. For instance, the ShortLink aggregate can enforce the Unique Code Policy when creating a link (e.g., by checking the code’s uniqueness in storage or by using a generation strategy that guarantees uniqueness).

Hotspots

🔴 Red sticky notes

As with any design, there are open questions and potential problem areas. The team tags these as red “hotspot” notes – things to watch out for or design carefully.

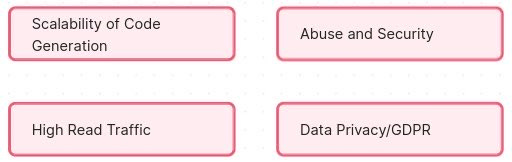

Scalability of Code Generation: Will generating unique short codes become a bottleneck? If they use a single counter or algorithm, can it handle many requests in parallel without collisions?2 They highlight the need for a robust key generation strategy (we’ll revisit this in Storage & Data Modeling).

High Read Traffic: A short URL might get extremely popular (imagine a viral link) and receive hundreds of hits per second. How will the system handle that load on the redirect path? This foreshadows caching and load balancing needs to meet latency NFRs.

Abuse and Security: URL shorteners can be misused to hide malicious links. The team doesn’t want to forget about security – e.g., they might need a way to scan or blacklist dangerous URLs (perhaps using an external service). This is a hotspot for later consideration so that “smart” doesn’t become “scam” – they add a note to incorporate safety measures (like not shortening known bad domains).

Data Privacy/GDPR: Since they plan to collect analytics, they need to consider what user data is collected and stored. This might be beyond a basic design, but Andy notes it as a point: if they log IP addresses or locations, privacy laws could apply. They agree to keep personally identifiable info out of their initial design (just aggregate counts).

Calling out these hotspots early helps them remember to address these points in the design. As Andy says, “Red notes mean no surprises later!”

Bounded contexts

🧩 Puzzle pieces

Finally, the team groups their domain into logical bounded contexts – essentially sub-domains that can be designed and understood independently. Given their discussions, two main contexts emerge.